A giant touchscreen takes up most of one wall in a room at the Curiosity Lab, in Peachtree Corners, Georgia. The figure standing in front of it can see live camera feeds from around the area, including several junctions and pedestrian crossings, some roundabouts and even a fountain in a public park. Another view shows a live map of traffic congestion and construction sites from the Georgia Department of Transportation. Yet another focuses on a single junction, with a computer algorithm labelling objects as cars, motorcycles or people. Its accuracy fluctuates: overhead traffic signals swinging in the breeze are labelled as motorcycles, and an area of shadow on a grassy strip is misidentified as a pedestrian.

Nature Outlook: Cities

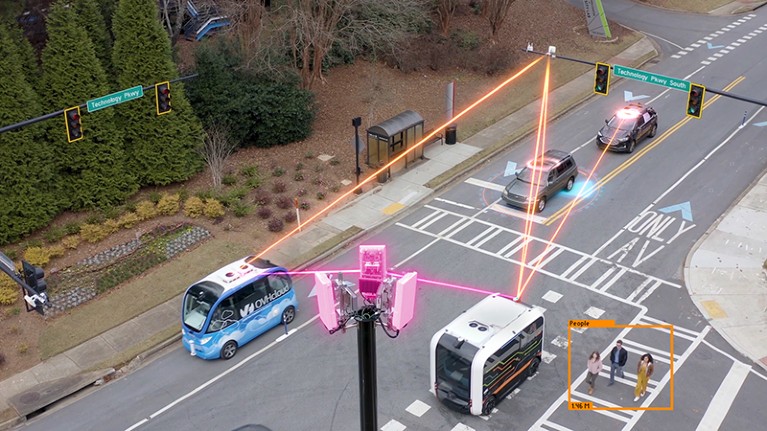

Curiosity Lab, an economic-development initiative in a suburb of Atlanta, calls itself a “smart city living laboratory”. Situated in the 200-hectare Atlanta Tech Park, it features a 4.8-kilometre stretch of roadway dedicated to trying out autonomous vehicles (AVs) and associated sensors, cameras and data networks. Instead of being an isolated test track, the road is part of a city street that carries more than 14,000 cars every day. This allows researchers from companies and academia to road-test not only AVs, but also a system powered by camera feeds, networked traffic signals and lidar sensing — the laser-based version of radar — that enables cars to talk to each other and to city infrastructure.

Beep, a start-up from Orlando, Florida, has tested its autonomous shuttles on this roadway. T-Mobile, the country’s second-largest wireless telecommunications company, is using 5G connections to investigate what new products both it and its customers might offer based on the technology, including AVs, drones and other robotics. In the next building, a garage houses three fully driverless sport utility vehicles (SUVs) developed by May Mobility of Ann Arbor, Michigan. These are equipped with lidar on the roof and cameras on each side to see all around the vehicles. In September, May Mobility launched a partnership with the car-hailing service Lyft to offer the driverless cars in midtown Atlanta on a limited basis.

“This is a huge part of why we do what we do,” says Valerie Chang, managing director of Curiosity Lab, standing next to one of the SUVs. “Having a live deployment on this scale where you’re in a real city with real roads and real intersections” makes it easier for companies to win contracts, she says. They can say “we actually did it in a real city on a real road”.

At Curiosity Lab in Atlanta, Georgia, vehicles, cameras and traffic signals can be connected wirelessly.Credit: Curiosity Lab

Getting smart

Peachtree Corners is not the only location where researchers are running trials to discover the future of urban mobility. Cities from San Francisco and Singapore to London and Lisbon are branding themselves as ‘smart cities’, on the basis of their ability to collect and use the ocean of data that a modern city generates. And transportation is a key application.

Some researchers think that sharing data between vehicles and infrastructure will move the world beyond today’s modest technological status quo, in which a handful of driverless taxis are navigating city streets. The future will belong to connected and autonomous vehicles (CAVs) that will base their driving decisions on information they share with each other and with roadside base stations. The pay-off of such automation will be improvements in safety, travel time and fuel economy. The CAVs, in turn, could be part of a larger vision in which public buses, trains, electric scooters, rental bicycles, delivery drones, mobile phones and even electric helicopter-like taxis all work together to make it easier for people and goods to move through a city.

Henry Liu, a civil engineer and director of the University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute in Ann Arbor, runs MCity, a 13-hectare test facility similar to Peachtree Corners. His lab is working with the city of Ann Arbor on a Smart Intersections Project that includes the installation of sensors and data-transmitting roadside units at half of the city’s 150 signal-controlled junctions. MCity is funded by a US$10-million grant from the US Department of Transportation and matching grants from corporate partners, including car-makers Ford and Toyota, and chip manufacturer Qualcomm.

Drones and ground robots take part in tests at MCity at the University of Michigan.Credit: Marcin Szczepanski/University of Michigan College of Engineering

The project is collecting data on objects or animals that show up in the road and that might require a reaction from a driving algorithm. Collisions at these junctions are rare, but near-misses happen much more often, Liu says. Researchers have therefore trained an algorithm to pick out the near misses from the data to see if they can learn anything that might help AVs to avoid crashes.

Liu expects more widespread deployment of AVs to come quickly. “I am very enthusiastic about this,” Liu says. “There are still some technical challenges, but I think in the next few years, these should be resolved.” Although limited to certain areas for now, self-driving taxis controlled by Waymo of Mountain View, California, have become a common sight on the streets of San Francisco and Los Angeles in California and Phoenix, Arizona. The company is planning to expand outside the United States to cities such as Tokyo and London.

Better connected

Christos Cassandras has a vision for how transportation should be networked in a future smart city. Cassandras, an electrical and computer engineer who heads the division of systems engineering at Boston University in Massachusetts, thinks that ideally “every car can communicate with each other and exchange information — their position, their velocity and potentially other things like destination, so we can then also optimize the routing of vehicles in an entire network”. This interconnectivity, he says, will enable vehicles to route themselves around the city in the most efficient and safest way possible.

An estimated 94% of US traffic collisions are attributable to human error, according to the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Letting computers do the driving could reduce that number by as much as half, Cassandras says. “Computers don’t sleep. Computers don’t blink. They don’t drink.” They can also process warnings of lane closures or accidents faster than humans can.

Opportunities to reduce road collisions are myriad. Vehicle-to-infrastructure systems, in which sensors or cameras along the road provide information to self-driving cars, could give a clearer picture of what is happening around them. A camera mounted on a light pole, for example, could spot a cyclist approaching from a side road and warn the car early. Vehicle-to-vehicle connectivity would allow cars to inform each other of their positions, speed and intended movements, so they would not have to guess what the others are doing.

Cassandras is working on a system that uses blockchain to let CAVs negotiate with nearby cars to execute manoeuvres. Cars would start their journey with a digital toll for using the roadway, and the cost would increase or decrease depending on whether they took cooperative action. For instance, cars that allow another to merge in front of them, to benefit the overall traffic flow, could earn micropayments, probably in a virtual currency. “The biggest challenge is not the technological implementation, but rather how to avoid gaming of the system by smart users,” Cassandras says, such as deliberately setting up situations in which they could agree to cooperate to accumulate cash.

Decisions about what to do would still belong to the algorithms in individual cars, says Andreas Malikopoulos, a mechanical engineer who directs the Information and Decision Science Laboratory at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. His lab is developing control algorithms to make use of the information shared between vehicles. They use a scale model of a city, with tiny AVs and drones, to test some of their ideas.

A model with tiny AVs and drones is used to test data-sharing algorithms at Cornell University.Credit: Andreas Malikopoulos

Malikopoulos’s approach is based on having a computer acting as a coordinator at each junction, collecting information from all the nearby vehicles and sharing it, so the vehicles can react accordingly. He likens the system to an air-traffic controller, providing pilots with constant updates as they near the airport. “It doesn’t make any decisions for your car, but it gives you information,” he says. A controller in the car can then use this information to compute the optimal speed to arrive at a junction when it is clear.

If cars could cross junctions safely without having to stop, they could avoid the deceleration and subsequent acceleration that cause much of the fuel consumption in today’s vehicles, Malikopoulos says. Coordinating cars’ speed could also help pedestrians by engineering gaps in traffic so that walkers can cross roads, and it might negate the need for some expensive traffic lights. The system could give priority to emergency vehicles, too — but if the traffic is flowing easily, it might not have to. “Let it go with the flow,” Cassandras says.

Connected vehicles face a chicken-and-egg problem, Liu says. Only when enough of them are on the road exchanging information will riders and cities see the benefits, but without an immediate pay-off, people might be reluctant to spend money on them. A simulation run by Zheng Xu, a civil engineer at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, found that road safety would greatly improve once CAVs make up more than 20% of cars on the road (Z. Xu et al. Accid. Anal. Prev. 215, 108011; 2025). At around 70%, collision rates in the model bottomed out at 86% lower than without any connected vehicles.

Even the 20% in Xu’s simulation is a lot of cars. However, Cassandras argues that just a few CAVs can start to positively affect traffic. One vehicle could reduce the speed of those behind it simply by slowing down, and if it does so gradually, human drivers might not even notice. A CAV in each lane, working together, could impose order on a whole road.

Xu’s modelling also suggests that there might be a point at which the safety advantages drop off. When more than 70% of vehicles are CAVs, collisions started to rise again. The problem, Xu explains, is that when there are too many vehicles running on similar algorithms, they become less resilient to unexpected actions from the dwindling number of road users who are outside the network. For instance, CAVs could safely follow each other at closer distances than human drivers can, because they can coordinate their speed to avoid crashes. “But when most vehicles share these expectations, the system becomes vulnerable to rule-breaking behaviours by pedestrians, cyclists or human drivers,” Xu says.

Going multimodal

Private cars are far from the only means of transportation that urbanites use. Many cities are focusing on multimodal transportation, in which cars, e-bikes and e-scooters, buses, trams and trains all have a role.

In the twentieth century, multimodal systems were based on hubs, such as bus depots and railway stations, says Carlo Ratti, an architect and engineer who runs the Senseable City Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. This is being replaced by what he calls “multimodality on the go”, powered by real-time data. “You might grab a floating scooter to get to the subway, as I always do in Paris,” Ratti says. “You leave your Uber Pool and bike the last 500 metres.”

Broad adoption of shared autonomous vehicles could free up space currently used for car parking. Credit: Gregory Rec/Portland Press Herald via Getty

“The bigger vision is a moving web,” he says. “Trains, buses, AVs, bikes and micromobility, all stitched together with data.” This is already possible to some extent with existing apps. Google Maps, for instance, offers driving routes based on current traffic, as well as routes on public transport that combine buses and trains. Ratti would like apps in more cities to include real-time information for all modes of transport. Another possibility, Cassandras suggests, is incorporating police reports and crime statistics to generate the safest route.

Ratti would also like to see “truly seamless single ticketing”, in which a person could pay for an entire journey in one transaction, even across multiple operators. This could make it possible to offer financial incentives to users to choose “socially optimal” routes, says Malikopoulos. This might mean reducing prices on less-busy routes during peak hours of the day to spread the strain on the transportation network. “The traveller, of course, will be entitled to make their own decisions,” Malikopoulos says.

In January, the metropolitan Washington DC area took a step towards encouraging socially optimal commuting with the release of the CommuterCash app. People travelling in Washington DC and Maryland can earn points for actions such as cycling or carpooling that reduce congestion and improve air quality. Those points can be redeemed for cash and gift cards, or applied as credits for the Washington Metro, the local bike-share service or tolls in Virginia. The group behind the scheme — an alliance of regional transportation providers known as Commuter Connections — also helps to match people for carpooling, and offers an emergency ride home to people who commute by carpool, bicycle, public transport or on foot at least twice a week.

If and when autonomous vehicles join the transport mix in cities, there are considerable potential benefits to them being shared, rather than privately owned — not least, a greatly reduced need for parking spaces. Most cars sit idle for 95% of the time, says Ratti. Replacing private vehicles with driverless robotaxis could free up a lot of space that is currently used to park cars between journeys. “It would be nice if we could turn all this real estate into things like hospitals, schools and movie theatres,” Cassandras says.

In 2020, Ratti and his colleagues used traffic data from Singapore in 2018 to model the effect of having shared AVs in almost constant use (D. Kondor et al. Sci. Rep. 10, 15885; 2020). They found that relying on robotaxis could reduce the number of cars on the road from 676,000 to 89,000, and cut the need for parking spaces from 1.37 million to 189,000 — a reduction of 86%. The trade-off was a 24% increase in traffic, because robotaxis not in use spent more time hunting for rarer parking spaces, but a less-severe 57% reduction in parking spaces could mostly mitigate this.

In the end, researchers say, the future of transportation comes down not so much to technological advances as policy decisions. It rests on whether local governments will spend money on infrastructure to improve their citizens’ commutes; on whether vehicle manufacturers will agree to make their systems operate with one another; and on whether federal governments will reward manufacturers of connected vehicles with better crash-avoidance ratings than other vehicles. “It’s not so much the technology, but the political will, the economics,” Cassandras says.

Ratti agrees. “AVs could either help or hurt cities,” he says, “depending entirely on how we deploy them and the political decisions we make.”