In Stranger Things, the supernatural villain Vecna rules a nightmarish parallel world called the Upside Down. Credit: Netflix/Everett/Shutterstock

Throughout its five seasons, the Netflix show Stranger Things follows a ragtag group of teenagers and their parents as monsters from another universe — unleashed by the secret work of a government laboratory — wreak havoc on a quaint, fictional town in Indiana.

Don’t worry, Demogorgons, Shadow Monsters and psychokinetically gifted 12-year-olds are strictly fictional creations. But the ‘parallel universe’ concept at the core of the show — which is set to conclude its nearly decade-long run at the end of this year — comes from a real scientific theory. And it’s been hotly debated by physicists over the past 75 or so years.

‘Many worlds’ interpretation

Although the series is as much in the realm of fantasy as science fiction, Stranger Things nods to many concepts of basic physics. Principles of electromagnetism explain haywire compasses, as well as magnets that spontaneously fall off a refrigerator. And in the third season, the characters save the world by using Planck’s constant during their quest to close a gate to the other universe, called the Upside Down (although the show uses the 2014 value for Planck’s constant, which wouldn’t have been standard in the 1980s setting).

Physicists disagree wildly on what quantum mechanics says about reality, Nature survey shows

Perhaps the most prominent physics phenomenon mentioned in the programme, however, is the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. After deducing that their friend might be stuck in the Upside Down, three pre-teen-boy protagonists ask their science teacher how they could travel there. He responds, “You guys have been thinking about Hugh Everett’s many-worlds interpretation, haven’t you?”

In the 1950s, the US physicist Hugh Everett really did propose such an explanation for modern physics, and his theory has been collecting devotees ever since. Everett’s work makes sense of a concept that has long baffled quantum physicists: the measurement problem. The question is how a quantum system can seem to be in two states at once — an electron that is simultaneously in two different locations, for example — until the moment the system is observed or measured, when all at once it’s in only one of those states.

The most popular explanation for this conundrum, called the Copenhagen interpretation, says that the unobserved electron exists in a hazy quantum state of both options, described only by probabilities, until suddenly, on measurement, it ends up in one. Everett poses an almost fantastical alternative: the electron really exists in both states at once, and after the measurement, an observer sees only one state because the universe branches in two, with each outcome existing in a different world. The countless quantum states of all the world’s particles create an infinite number of universes: hence, many worlds.

Controversial theory

For many physicists, this idea is a bit far-fetched, particularly because if these many worlds can’t interact, then there’s no way to prove or falsify the theory, says Jorge Pullin, a theoretical physicist at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge.

But for others — including Sean Carroll, a theoretical physicist at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, who has worked as a science adviser for science-fiction films — the many-worlds interpretation is the most elegant explanation out there. “There are a lot of people who think this is the simplest version of quantum mechanics, and it fits all the data,” he says. Of the many explanations of quantum theory, many worlds is currently the third most popular among quantum physicists, a Nature survey found earlier this year.

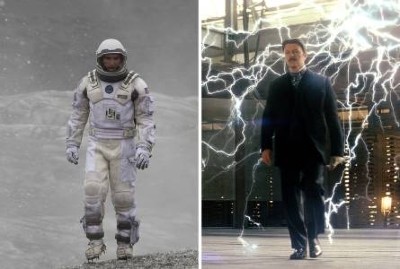

The sci-fi films that physicists love to watch — from Interstellar to Spider-Man