12 March — A small piece of land yields bats with a trove of new coronaviruses

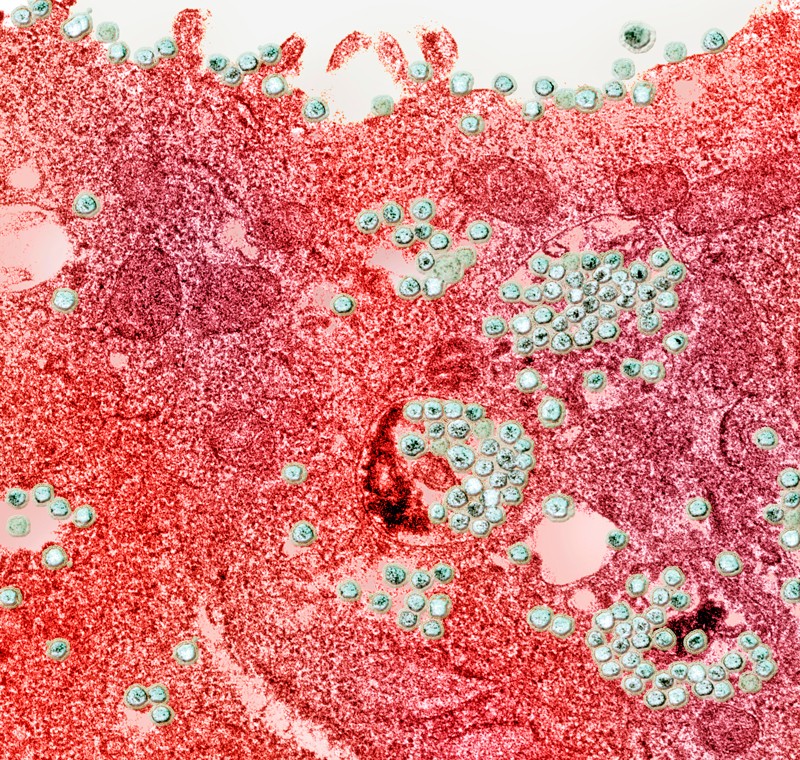

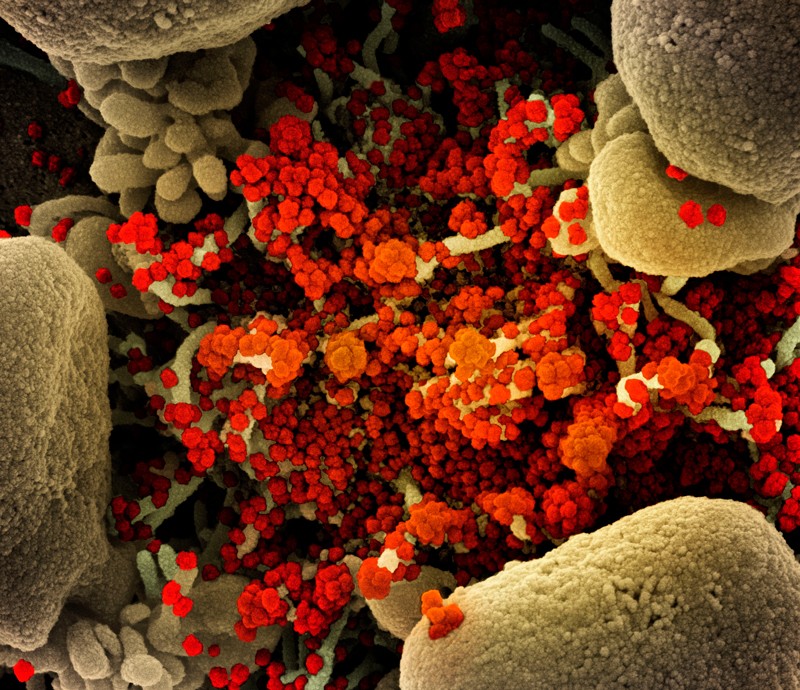

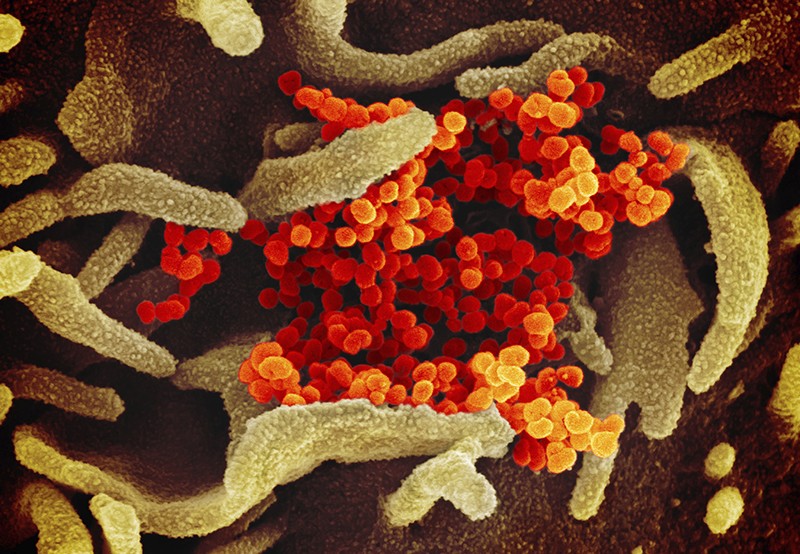

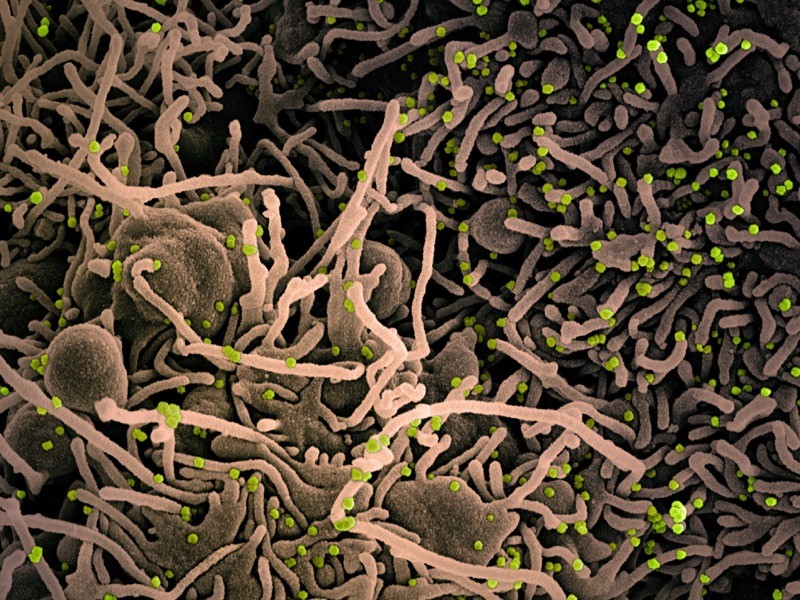

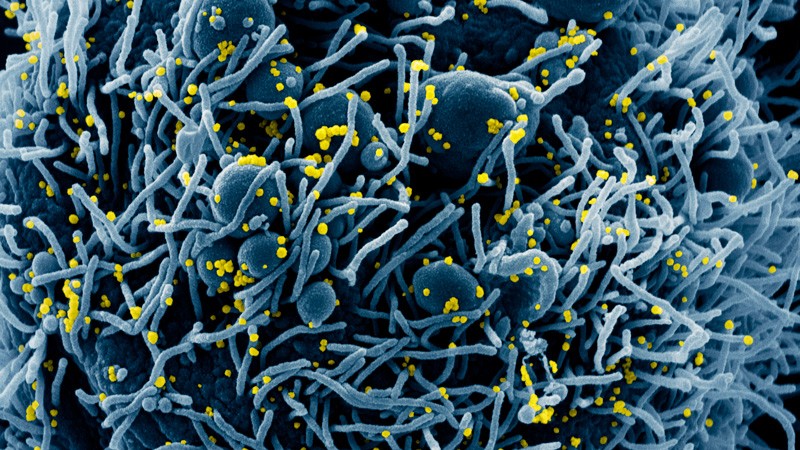

Bats in the province of Yunnan in southern China have yielded yet more coronaviruses closely related to the pandemic virus.

Weifeng Shi at the Shandong First Medical University & Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences in Taian, China, and his colleagues studied 302 samples of faeces and urine and 109 mouth swabs taken from 342 live bats between May 2019 and November 2020 (H. Zhou et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/gh73mk; 2021). The researchers trapped and released all the bats, which represented nearly two dozen species, in an area covering roughly 1,100 hectares — less than one-tenth the size of San Francisco, California.

From the samples, the team sequenced 24 coronavirus genomes, of which 4 were new viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2. One of the viruses isolated from a Rhinolophus pusillus bat shared 94.5% of its genome with the pandemic virus, making it the second-closest known relative to SARS-CoV-2. The closest known relative is a coronavirus called RATG13, which shares 96% of its genome with SARS-CoV-2 and was isolated from a Rhinolophus affinis bat in Yunnan in 2013.

The results suggest that viruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2 continue to circulate in bats and are highly prevalent in some regions, the researchers say. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

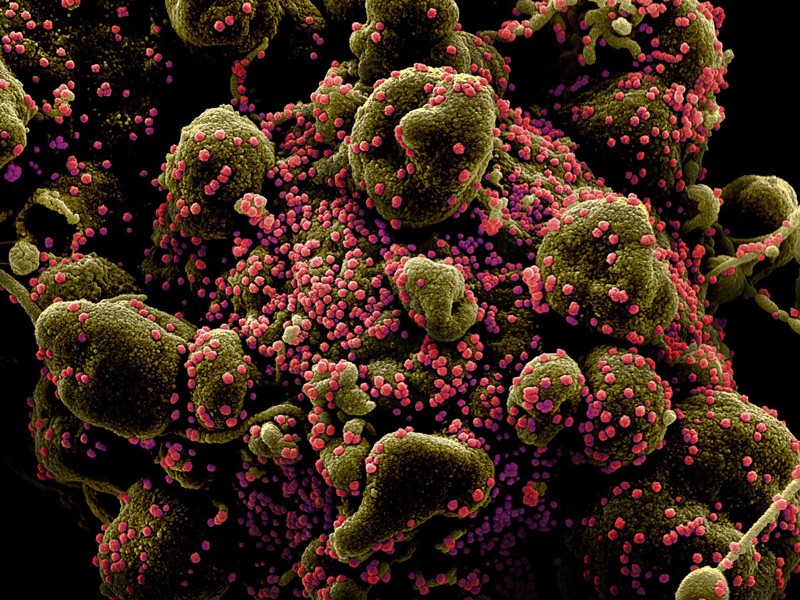

11 March — Viral variant causes a more deadly form of COVID

People infected with the coronavirus variant called B.1.1.7 are at a higher risk of dying than are people infected with other circulating variants, regardless of their age, sex and pre-existing health problems.

Daniel Grint at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and his colleagues studied the health records of 184,786 people in England who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 between 16 November 2020 and 11 January 2021. Of these individuals, 867 died by 5 February 2021 (D. Grint et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fzwq; 2021).

The researchers found that for three people who died within a month of testing positive for a previously circulating viral variant, some five died after testing positive for B.1.1.7. The risk of death increases with age and the presence of pre-existing health problems, and men are at higher risk of dying than women.

First detected in the United Kingdom, B.1.1.7 is now the dominant variant there and is spreading widely across Europe. Without control measures and vaccines, the variant could cause a more deadly pandemic than previously circulating versions of the virus, the researchers say.

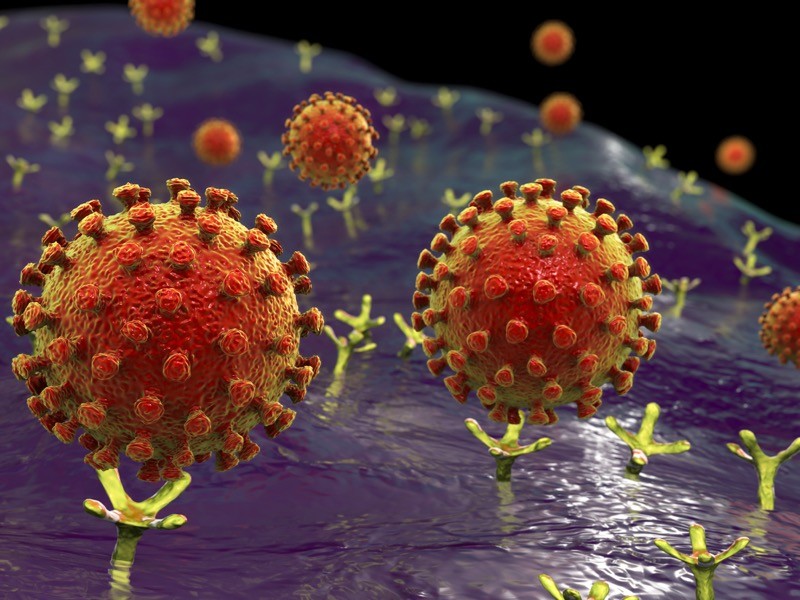

10 March — A worrisome coronavirus variant brings hope for better vaccines

People infected with a fast-spreading coronavirus variant mount an immune response that can fend off multiple SARS-CoV-2 strains.

Scientists first identified the SARS-CoV-2 variant called B.1.351 in South Africa in late 2020. They have since linked it to reinfections and found hints that several vaccines are less effective against it than against SARS-CoV-2 variants circulating earlier in the pandemic.

Penny Moore at the National Institute for Communicable Diseases in Johannesburg, South Africa, and her colleagues assessed the antibody responses mounted by 89 people who were infected with B.1.351 and were admitted to hospital (T. Moyo-Gwete et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/fzq5; 2021). The team found that these participants’ antibody levels were similar to those in people infected with earlier strains.

The team then pitted antibodies from people infected with B.1.351 against a form of HIV modified to use the coronavirus spike protein to infect cells. The antibodies were able to inactivate viruses incorporating the form of spike protein found in B.1.351, earlier strains, and an emerging variant identified in Brazil called P.1.

The results suggest that vaccines based on B.1.351’s genetic sequence might protect people from multiple strains of the coronavirus, the authors say. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

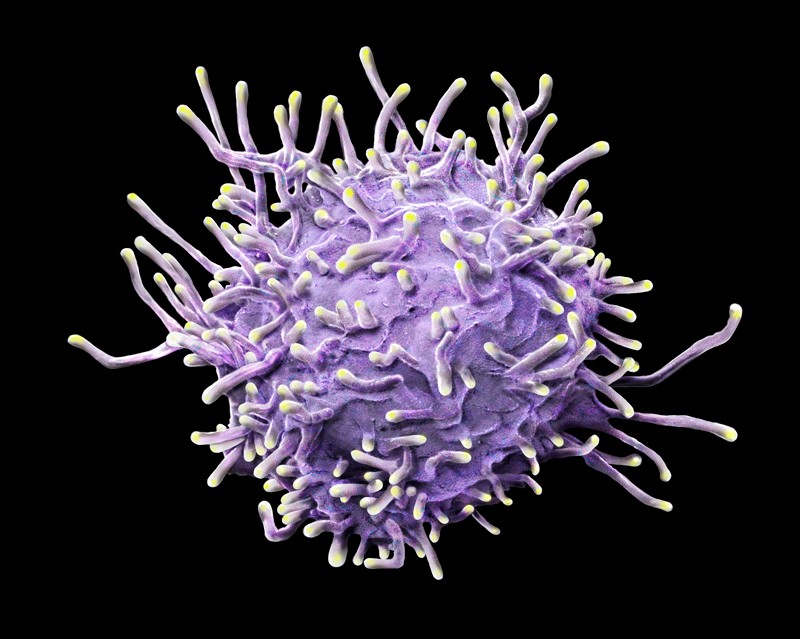

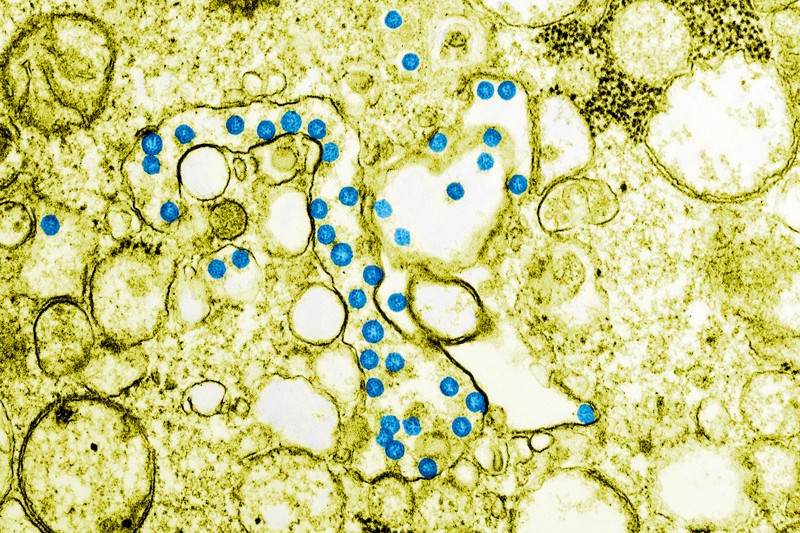

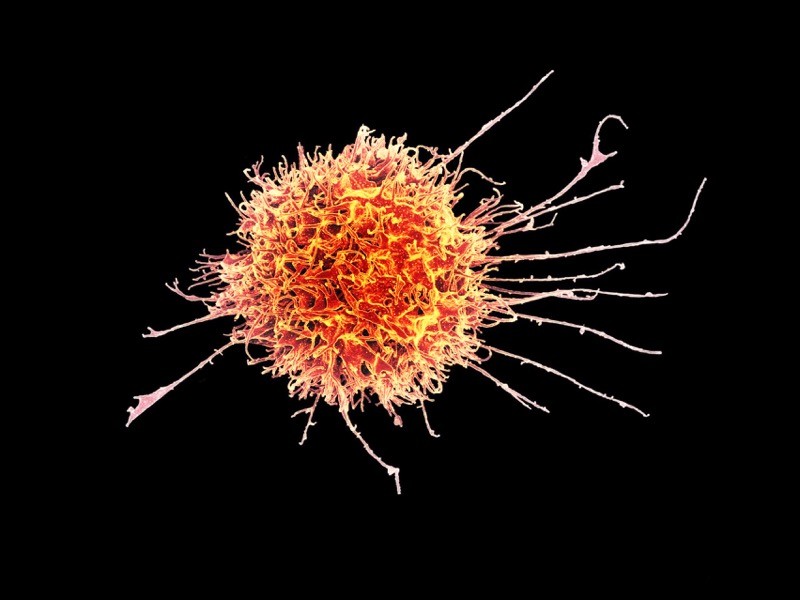

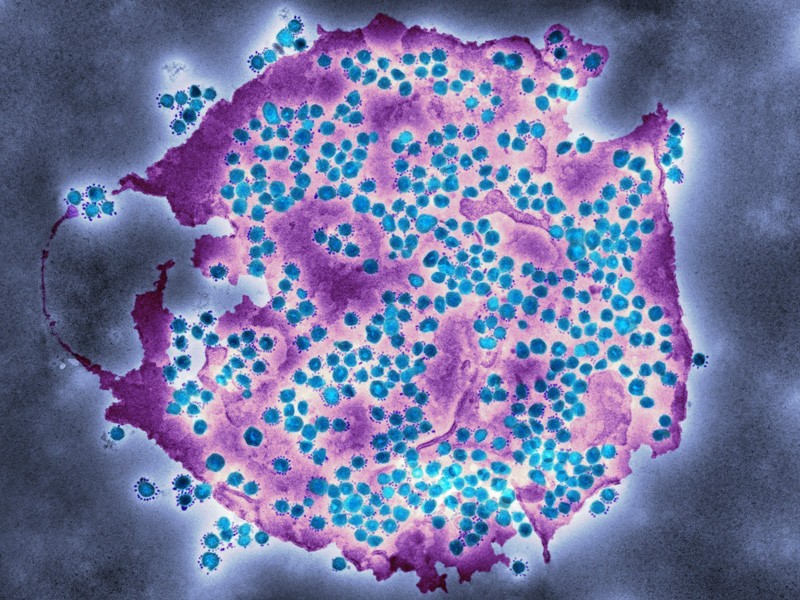

5 March — T cells might provide rescue from rampant coronavirus variants

Emerging coronavirus variants do not seem to elude important immune-system players called T cells, laboratory studies suggest.

Some recently discovered SARS-CoV-2 variants can partially evade antibodies generated in response to vaccination and previous infection,raising fears that vaccines will be less effective against the variants than against the original strain of the virus. Alessandro Sette and Alba Grifoni at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California and their colleagues looked at whether these variants’ mutations might also help them to evade T cells — a component of the immune system that is particularly important for reducing the severity of infectious diseases (A. Tarke et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/gh6tkp; 2021).

The team collected T cells from volunteers who had either recovered from infection with the ancestral SARS-CoV-2 strain or had received an mRNA coronavirus vaccine. The researchers then tested the cells’ ability to recognize protein snippets from four emerging variants, including the B.1.351 variant first identified in South Africa.

Most of the volunteers’ T cells recognized all four variants, thanks to viral protein snippets that were unaffected by the variants’ mutations. The results suggest that T cells could target these variants.

4 March — A new viral variant hits a COVID-ravaged city

A coronavirus variant detected in the Brazilian city of Manaus might be driving reinfections and the city’s second wave of COVID-19.

During the first wave of the pandemic, Manaus experienced one of the world’s highest infection rates: an estimated two-thirds of residents were infected by October 2020, leading some researchers to predict that population-wide immunity might cause new infections to tail off. But in January 2021, researchers identified a novel coronavirus variant, called P.1, during a period of rising hospitalizations in the city and linked the variant to a few cases of reinfection.

To characterize the variant further, Nuno Faria, at Imperial College London, and his colleagues analysed viral genomes collected from 184 human samples in Manaus between November and December (N. R. Faria et al. Preprint at https://go.nature.com/3sor3jj; 2021). The variant harbours 17 mutations that alter SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Among the alterations are changes in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that have been previously linked to increased transmission and immune evasion.

By modelling the spread of P.1 and its possible effects during Manaus’ second wave, the researchers estimated that the variant was 1.4–2.2 times more transmissible than other lineages and that it was able to evade some of the immunity conferred by previous infections. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

3 March — Kids in the classroom could mean COVID at home

Living with children who are attending school in person raises an adult’s risk of developing COVID-19 symptoms, but only if schools don’t implement appropriate control measures, according to a large online survey in the United States.

Justin Lessler at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland, and his colleagues analysed responses to a Facebook survey completed in late 2020 and early 2021 by more than half a million people living with school-aged children; half of these respondents had children attending school in person, either full-time or part-time (J. Lessler et al. Preprint at medRxiv; https://doi.org/fxv6; 2021).

The researchers found that adults living with kids — especially high-school students — who went into school were more likely to report COVID-19 symptoms or test positive for SARS-CoV-2. But the researchers also found that schools could eliminate that risk entirely by implementing at least seven mitigation measures from a list that included requiring students and teachers to wear masks, preventing parents from entering schools and increasing the spacing between desks. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

2 March — Just one dose of vaccine protects against silent COVID infection

Asymptomatic coronavirus infections were four times less frequent in health-care workers who had received a single dose of a prominent COVID-19 vaccine than in their unvaccinated counterparts.

Michael Weekes at the University of Cambridge, UK, and his colleagues analysed the results of almost 8,900 SARS-CoV-2 tests taken by UK health-care workers without symptoms of COVID-19 (M. Weekes et al. Preprint at Authorea https://doi.org/fxkd; 2021). Study participants who were tested at least 12 days after receiving one dose of the vaccine developed by Pfizer of New York City and BioNTech of Mainz, Germany, had an infection rate of only 0.2%. By contrast, unvaccinated participants had an infection rate of 0.8%.

The team also noted that participants who showed evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection well after vaccination tended to have lower levels of the coronavirus in their bodies than did those who were infected and unvaccinated, although the result did not reach statistical significance. If corroborated, this would suggest that the few vaccinated health-care workers who do have an asymptomatic infection are less likely to infect other people than are unvaccinated workers who become infected.

The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

26 February — A COVID vaccine passes a real-world test with flying colours

The two-shot Pfizer vaccine is highly effective at preventing severe COVID-19, according to an analysis of more than one million people in Israel.

Ran Balicer at Clalit Health Services in Tel Aviv, Israel, and his colleagues matched 596,618 people vaccinated as part of a nationwide campaign with an unvaccinated ‘twin’ of the same age, sex, ethnicity and neighbourhood of residence. The pairs also had a matching number of medical conditions and shared other characteristics (N. Dagan et al. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/fw7w; 2021).

The researchers found that, at 7 days or more after the second shot, Pfizer’s vaccine was 94% effective at preventing COVID-19 and 92% effective against severe disease. The results were consistent across all age groups, including in people aged 70 and older. The results were strikingly close to efficacy estimates from clinical trials, despite being based on jabs administered in less stringently controlled settings and more diverse populations, including people with multiple health problems.

The study also covered a period when the emerging variant called B.1.1.7 was circulating widely in Israel, which suggests that the vaccine is effective at preventing COVID-19 caused by that variant.

25 February — Trial hints that Pfizer vaccine could curb COVID transmission

A leading COVID-19 vaccine is highly effective at preventing SARS-CoV-2 infections, whether they cause symptoms or not — the strongest evidence yet that vaccines could control viral spread.

Large-scale trials of COVID-19 vaccines have focused on assessing their ability to prevent disease, but researchers also want to know whether the vaccines can prevent people from getting infected, even if they show no symptoms. Susan Hopkins at Public Health England in London and her colleagues tracked the effectiveness of the vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech in 23,000 UK health-care workers who were already part of a long-term study of SARS-CoV-2 immunity (V. J. Hall et al. Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/fw7v; 2021). Participants were tested regularly for SARS-CoV-2, regardless of their symptoms.

The vaccine was 70% effective at preventing both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections in the period beginning 3 weeks after the first dose; this grew to 85% shortly after a second dose of the RNA vaccine. This finding is the first evidence that Pfizer’s vaccine might block transmission, the researchers say. The study has not yet been peer reviewed.

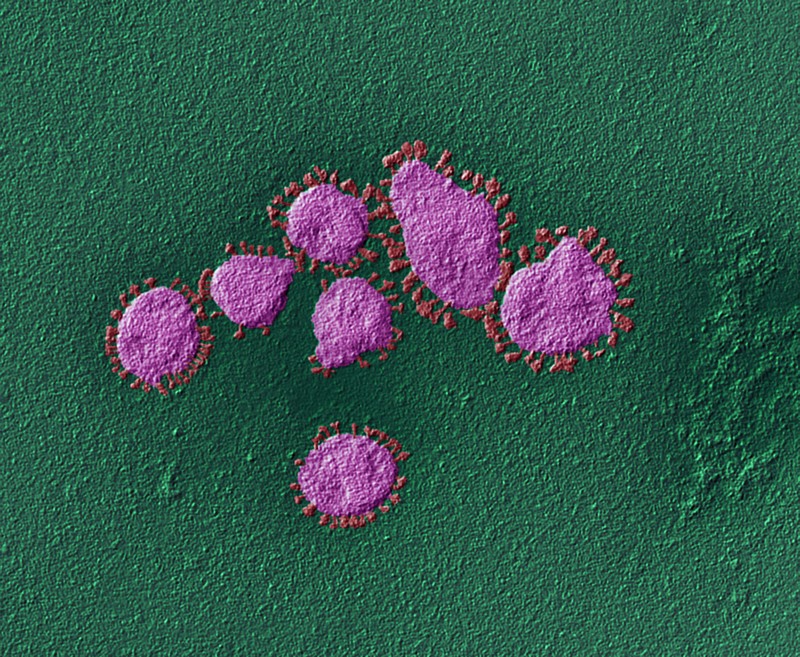

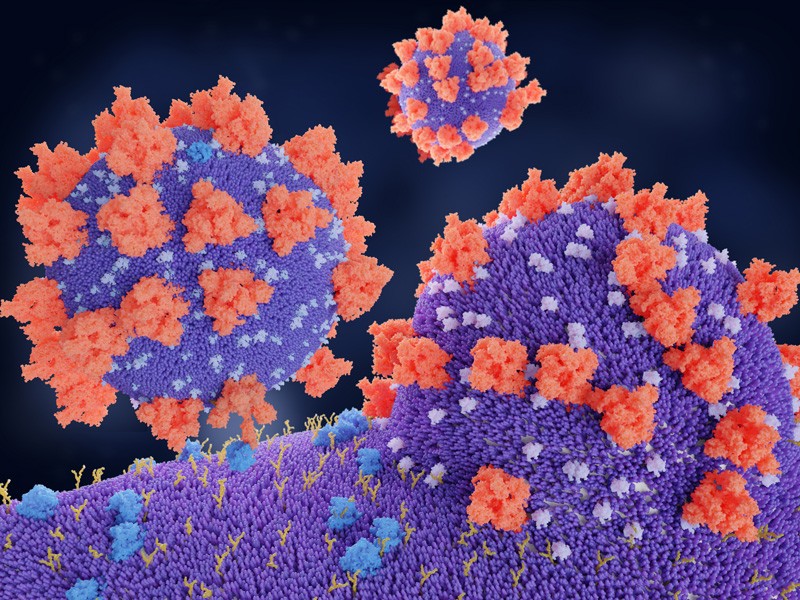

23 February — Viral variant is less susceptible to a COVID vaccine’s effects

Coronaviruses engineered to contain mutations from a worrisome variant partially blunt the immune protection offered by a prominent vaccine.

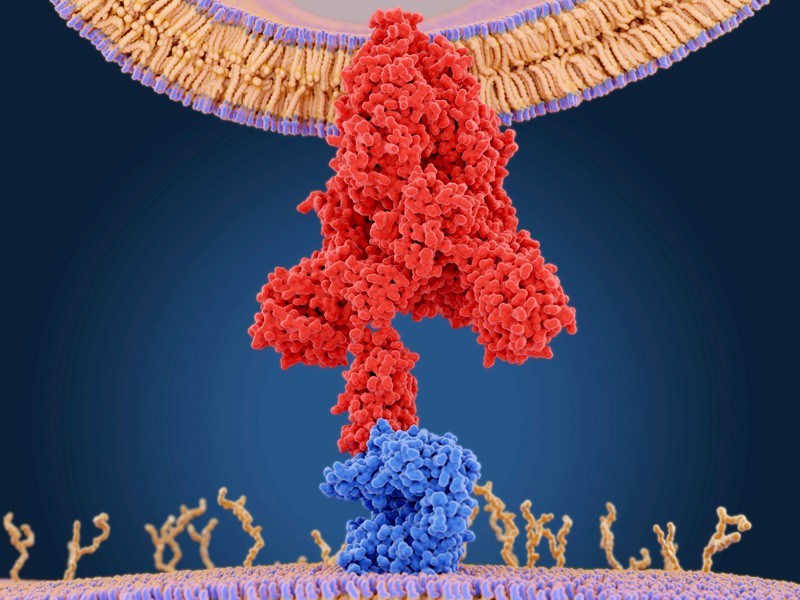

In recent months, studies have raised the possibility that the potent antibodies summoned by vaccines could be less effective against emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants than against older versions of the virus. Most of this work stems from experiments not on SARS-CoV-2, but on viruses such as HIV that have been modified to contain SARS-CoV-2’s signature spike protein.

Pei-Yong Shi at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston and his colleagues engineered several variants of SARS-CoV-2, including one containing the same spike-protein mutations as a troubling variant called B.1.351 (also known as 501Y.V2) that was first identified in South Africa (Y. Liu et al. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/fwsc; 2021).

The team pitted the B.1.351-like virus against blood serum from people who had received two doses of the vaccine made by Pfizer and BioNTech in Mainz, Germany. Antibodies elicited by the vaccine neutralized the virus only one-third as effectively as they did a strain lacking those mutations.

The researchers traced most of the virus’s evasive ability to a trio of mutations in the portion of the spike protein that SARS-CoV-2 uses to adhere to host cells. However, it is not clear whether these changes make the vaccine less effective at preventing COVID-19.

22 February — A delayed second jab means better protection against COVID

A widely used COVID-19 vaccine is more effective if the second of its two doses is given after a long wait rather than a short one — a finding that supports a decision by UK public-health officials to space out the doses.

The two-dose vaccine developed by the University of Oxford, UK, and pharmaceutical firm AstraZeneca in Cambridge, UK, could be given to more people by lengthening the interval between jabs. To test the efficacy of this strategy, Andrew Pollard at the University of Oxford and his colleagues examined clinical-trial data from more than 17,000 people, half of whom received the vaccine and the other half a placebo (M. Voysey et al. Lancet https://doi.org/fwk7; 2021).

The team found that, for intervals greater than six weeks, the longer the gap between jabs, the better the vaccine protected against COVID-19. It was 55% effective in those who received their second dose less than 6 weeks after their first, and 81% effective in those whose second dose was more than 12 weeks after their first. The team also found that a single dose of the vaccine had an efficacy of 76% for the first 90 days after vaccination.

19 February — Longer infections could fuel a variant’s quick spread

Preliminary findings suggest that B.1.1.7, a SARS-CoV-2 variant first identified in the United Kingdom, might be more transmissible because it spends more time inside its host than earlier variants do.

Previous studies have estimated that B.1.1.7, which is now spreading rapidly in a number of countries, is roughly 50% more contagious than earlier coronavirus variants are. Yonatan Grad at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues examined the results of daily SARS-CoV-2 tests on 65 people infected with SARS-CoV-2, including 7 infected with B.1.1.7 (S. M. Kissler et al. Preprint at https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37366884; 2021). The team looked at how long the virus persisted, and the amount of virus present at each time point.

In people infected with B.1.1.7, infections lasted an average of 13.3 days, compared with 8.2 days in people with other variants. There was little difference in the peak concentrations of the virus between the two groups.

These findings hint that B.1.1.7 is more easily transmitted than other variants are because people who catch it are infected for a relatively long time, and can therefore infect a larger number of contacts. This suggests that longer quarantine periods might be warranted for individuals infected with this variant. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

16 February — ‘Robin’ leads a flock of new US COVID variants

Seven newly identified coronavirus variants in the United States share a similar mutation, but the significance of this change is not yet clear.

Coronavirus variants emerging in a range of geographical locations seem to share certain mutations — possible evidence that the changes aid transmission. Jeremy Kamil at Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center in Shreveport and his colleagues identified a new variant that they named Robin (E. B. Hodcroft et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fvs4; 2021). It carries a change called Q677P in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which the virus uses to bind to cells.

The lineage was first spotted in October and its prevalence has risen in some parts of the United States. It accounted for 27.8% of sequenced viruses in Louisiana and 11.3% in New Mexico between the start of December 2020 and mid-January 2021. The researchers identified six other variants — also named after birds, including Pelican and Bluebird — in the United States with a mutation at the same spot in the spike protein.

The mutation is located near a portion of the spike protein that must be cut to allow a viral particle to infect a cell, but the researchers say that laboratory studies might be needed to determine what the mutation does. The finding has not yet been peer reviewed.

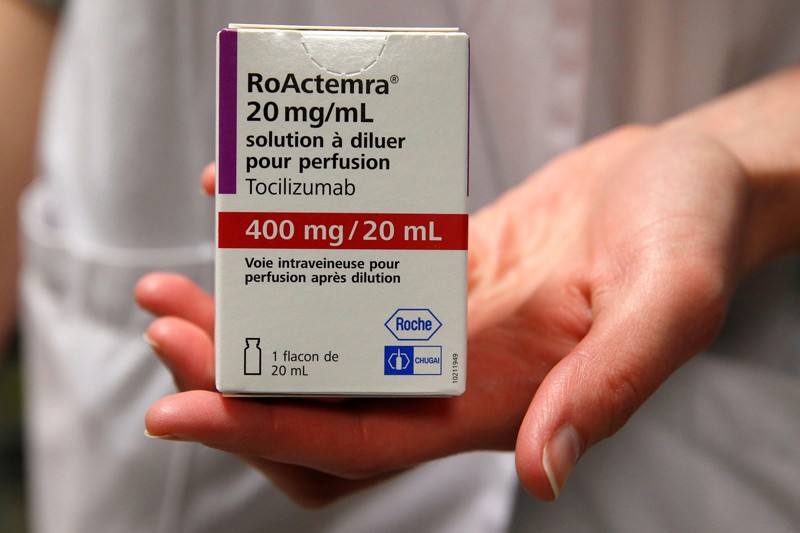

15 February — Drug can be a lifeline for people hospitalized for COVID

An anti-inflammatory drug can save the lives of people hospitalized for COVID-19 whose immune systems have gone into overdrive against the coronavirus. The drug also cuts the need for invasive ventilation, according to a large study.

Many people with severe COVID-19 symptoms show evidence of widespread inflammation. The drug tocilizumab is designed to dampen such an immune response, but previous clinical trials of its benefits in people infected with SARS-CoV-2 have been equivocal.

Peter Horby and Martin Landray at the University of Oxford, UK, and their colleagues compared more than 2,000 people treated with tocilizumab with a similar number who did not receive the drug (RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fvqj; 2021). Study participants were in hospital and receiving oxygen and had evidence of system-wide inflammation, and nearly all were also taking the steroid dexamethasone.

The authors report that 54% of people who received tocilizumab left hospital within 28 days, compared with 47% of those not taking the drug. An analysis showed that tocilizumab provided benefits on top of those from dexamethasone. The team estimates that roughly half of all people hospitalized with COVID-19 in the United Kingdom would benefit from the drug.

The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

12 February — Vaccines spur antibody surge against a COVID variant

One shot of either the Moderna or the Pfizer vaccine provokes a strong immune response against an emerging variant of SARS-CoV-2, according to tests in people who have recovered from COVID-19.

The mRNA vaccines made by Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Pfizer in New York City are highly effective at preventing COVID-19 caused by the original form of SARS-CoV-2. Andrew McGuire at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues collected blood from ten people who had recovered from COVID-19; they collected additional samples after the study participants had received a single dose of one of the two vaccines (L. Stamatatos et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ft9j; 2021). The researchers then examined the participants’ levels of neutralizing antibodies — which defend cells from infection — against the original version of SAR-CoV-2, which was first detected in Wuhan, China, and against B.1.351, the concerning new variant that was first identified in South Africa.

Before inoculation, nine of the ten individuals had neutralizing antibodies against the original virus, although the levels generated were highly variable. Antibodies from only five people could neutralize B.1.351. Following a single shot of the vaccine, however, participants’ levels of neutralizing antibodies against both forms of the virus increased by approximately 1,000-fold.

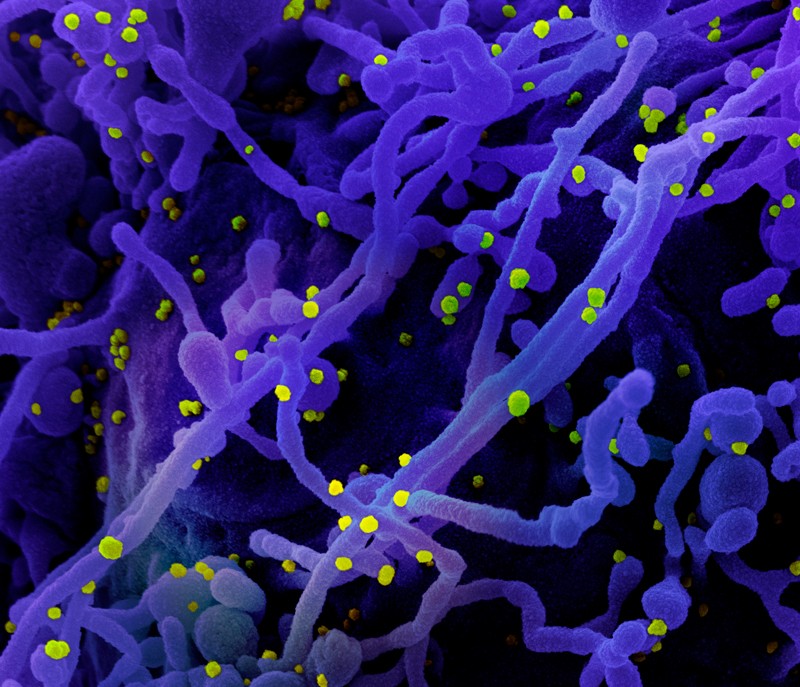

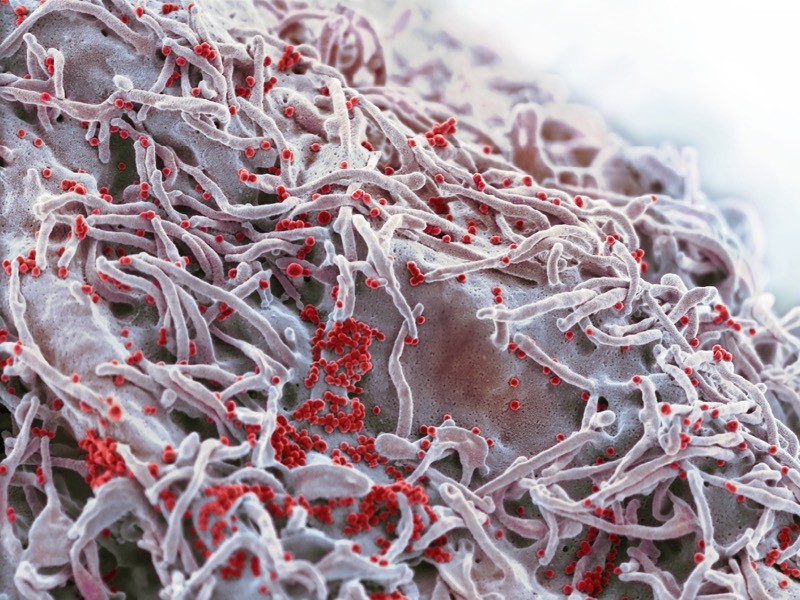

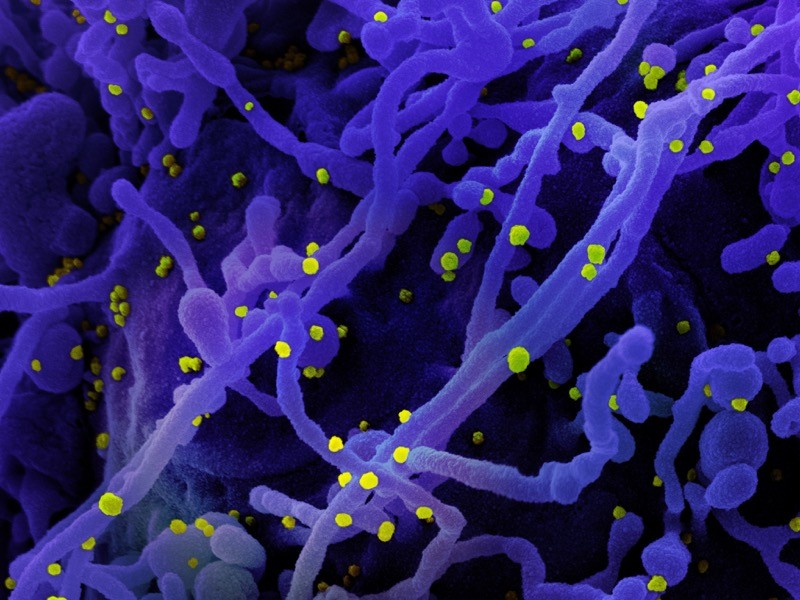

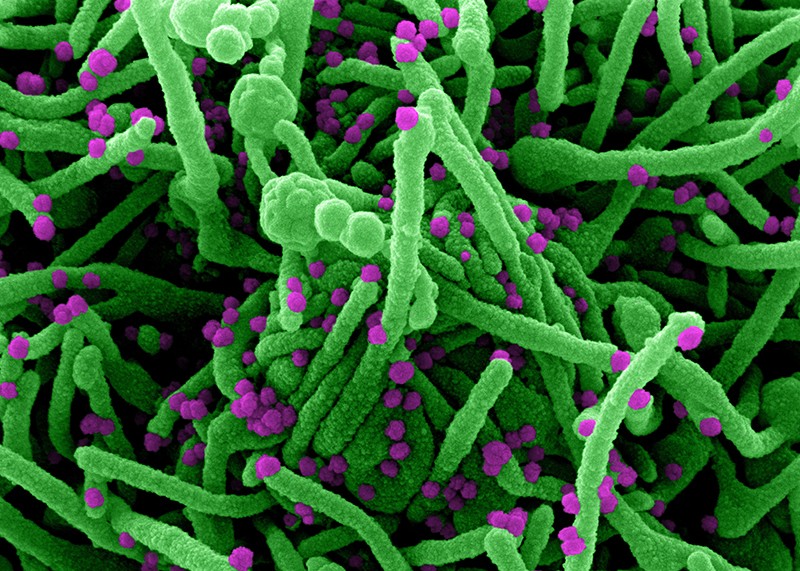

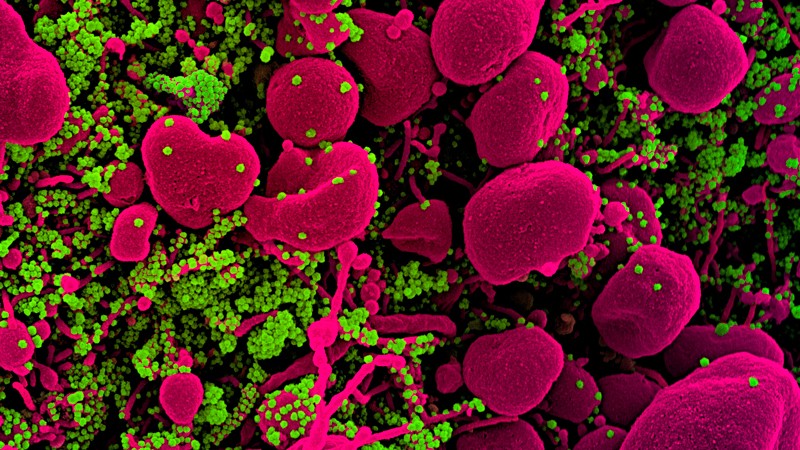

9 February — Nimble coronaviruses could leap straight from bats to humans

Some coronaviruses found in bats could jump directly to people without the need for further evolution in an intermediate animal host.

Victor Garcia at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and his colleagues implanted mice with human lung tissue and infected the tissue with various coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2 and two closely related coronaviruses isolated from bats. All of the viruses could efficiently multiply in the lung tissue (A. Wahl et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03312-w; 2021). The findings suggest that coronaviruses circulating in bats could directly infect people, and have the potential to cause the next pandemic.

The researchers also used the animal model to show that an oral antiviral drug known as EIDD-2801 could significantly reduce infectious particles of SARS-CoV-2 in the lung tissue. They say that the drug, currently in late-stage clinical trials, could be used to prevent disease as well as to treat people within a day or two of exposure to SARS-CoV-2.

8 February — Why it matters that COVID viruses are losing parts of their genome

Again and again, the new coronavirus has sloughed off small chunks of its genome, leading to changes in a viral protein that is frequently targeted by antibodies.

When evolution snips out a stretch of an organism’s genome, the change is called a deletion. Kevin McCarthy and Paul Duprex at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine in Pennsylvania and their colleagues searched a database of SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences and identified more than 1,000 viruses with deletions in the genomic region that encodes a protein called spike (K. R. McCarthy et al. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abf6950; 2021). The virus uses the spike protein to invade cells.

Further analysis showed that the deletions tended to crop up at a few distinct sites in the genomic region coding for spike. Some of the deletions have arisen independently multiple times, and some show evidence of spread from one person to another.

A powerful antibody against SARS-CoV-2 could not latch onto spike proteins harbouring some of the deletions that the team identified. But antibody mixtures collected from people who had recovered from COVID-19 could disable viral variants that had deletions.

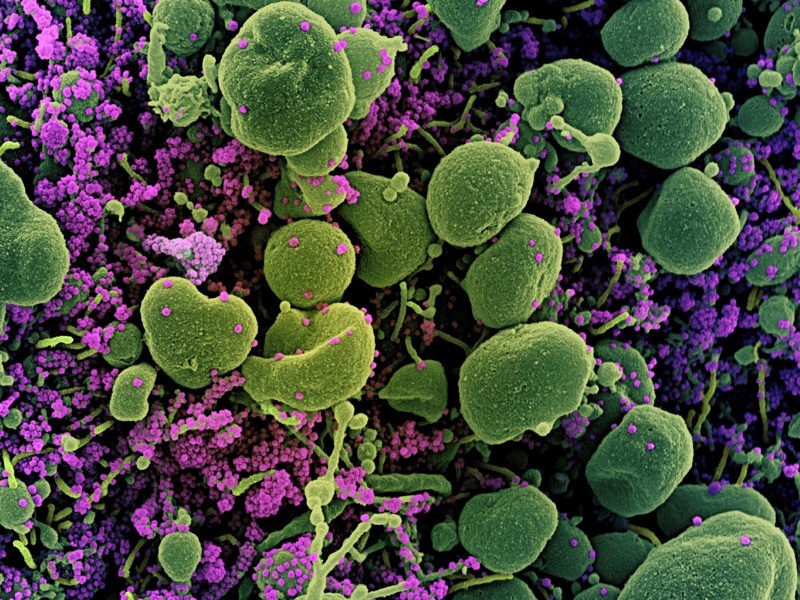

5 February — One man’s COVID therapy drives worrisome viral mutations

Antibody treatment for COVID-19 seems to have spurred mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 that infected a man with a compromised immune system.

In mid-2020, a man was admitted to hospital with COVID-19. He had been diagnosed with cancer in 2012; the illness and his treatment had probably weakened his immune system. The man’s COVID-19 was treated with two courses of the antiviral drug remdesivir and, later, two courses of convalescent plasma — antibody-laden blood from people who had recovered from COVID-19. He died 102 days after admission.

Ravindra Gupta at the University of Cambridge, UK, and his colleagues analysed viral genomes obtained from the man during his illness (S. A. Kemp et al. Nature https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03291-y; 2021). The viral populations in his blood changed little after remdesivir treatment. But after each course of convalescent plasma, the samples were dominated by viruses with a particular pair of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, the main target of the immune system.

Experiments showed that one of the mutations weakened the potency of the antibodies in the convalescent plasma, yet also reduced the virus’s infectivity. The second mutation restored infectivity. The potential for viral evolution means that convalescent plasma should be used cautiously when treating people with compromised immunity, the authors say.

4 February — What makes a person with COVID more contagious? Hint: not a cough

The amount of SARS-CoV-2 in a person’s body is a major factor in determining whether they are likely to transmit the virus to others, according to a study of nearly 300 infected people and their close contacts.

Most people with COVID-19 do not give it to anyone else, but some become ‘superspreaders’. To understand why, Michael Marks at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and his colleagues monitored 282 people, deemed ‘index cases’, who had recently developed mild symptoms of COVID-19. The team also monitored 753 people who lived with, cared for or otherwise had close contact with the index cases (M. Marks et al. Lancet Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30985-3; 2021).

Only one-third of the index cases transmitted the virus to a close contact. Those with a relatively high ‘viral load’, a measure of the amount of virus in the body, were much more likely to pass on the virus than were those with a low viral load. Index cases were no more likely to transmit the virus if they had a cough than if they didn’t.

The findings suggest that tracing the contacts of people with high viral loads is especially important, the authors say.

2 February — Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine shows high effectiveness

A vaccine that relies on modified cold viruses is more than 91% effective against symptomatic COVID-19, according to interim results of a clinical trial involving nearly 22,000 people.

Pathogens in the adenovirus group typically cause mild illnesses, such as the common cold. The Sputnik V vaccine developed at the Gamaleya National Center of Epidemiology and Microbiology in Moscow consists of two types of adenovirus, each carrying genetic instructions for the spike protein that SARS-CoV-2 uses to latch onto host cells. Use of two viruses could help to increase the immune response to the vaccination.

Denis Logunov at the Gamaleya centre and his colleagues analysed data from roughly 15,000 clinical-trial participants who had received an initial jab containing one type of adenovirus and, 21 days later, a booster jab of the second type of virus. The team also studied 4,900 participants who received two doses of a placebo (D. Y. Logunov et al. Lancet https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00234-8; 2021).

Starting from 21 days after the first jab, 16 symptomatic cases of COVID-19 — all mild — were recorded in the vaccine group. The placebo group incurred 62 cases, 20 of which were moderate or severe.

Preliminary evidence suggests that the vaccine starts to offer protection 16–18 days after the first dose, but the authors say more research is needed to confirm this early finding.

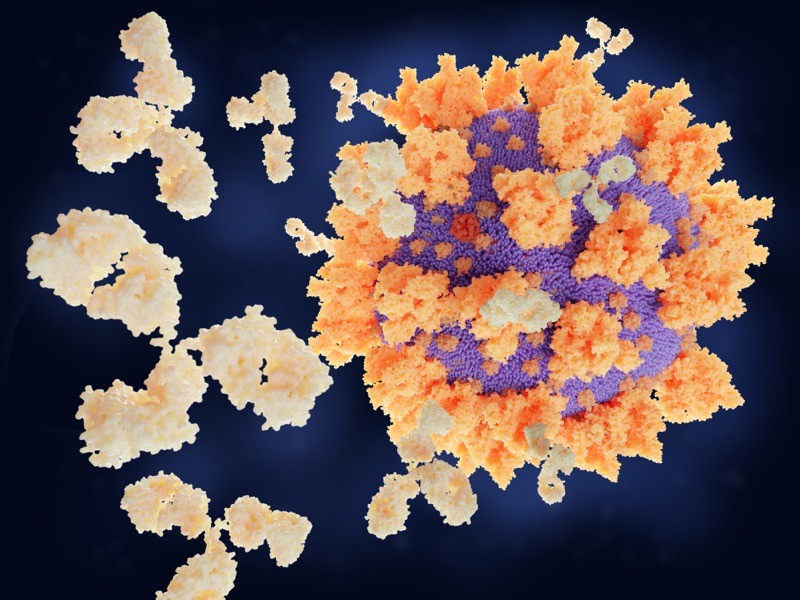

29 January — An antibody that clamps onto the COVID virus’s ‘Achilles heel’

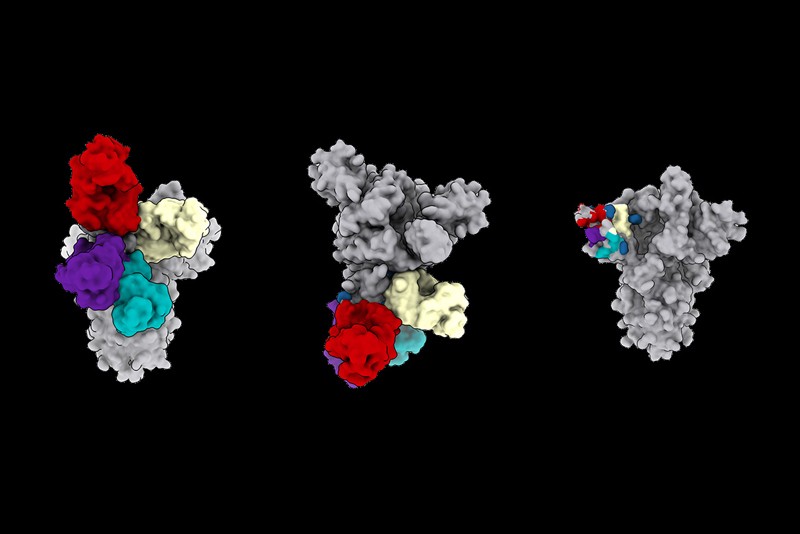

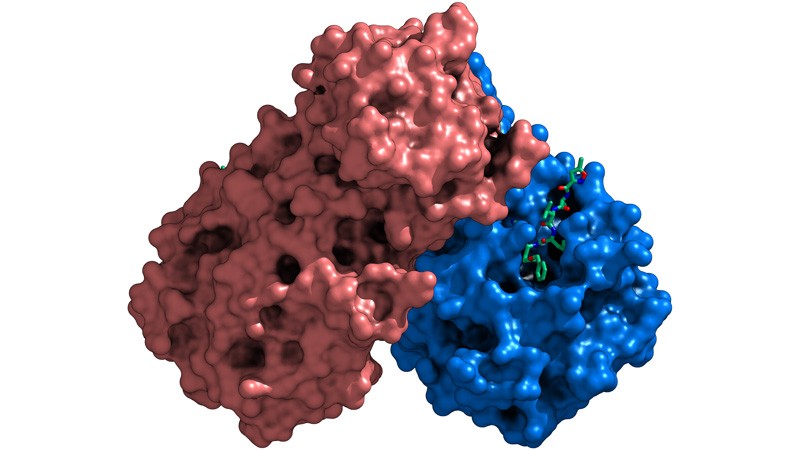

Scientists have engineered an antibody that effectively disables SARS-CoV-2 and closely related coronaviruses.

Laura Walker at the biopharmaceutical company Adimab in Lebanon, New Hampshire, and her colleagues isolated antibodies from the immune cells of a person who had recovered from a 2003 infection with the virus SARS-CoV, which is related to SARS-CoV-2 (C. G. Rappazzo et al. Science https://doi.org/fsbc; 2021). By tinkering with the structure of the antibodies, the researchers created one, called ADG-2, that was particularly effective at disabling SARS-CoV-2 in a lab dish.

The engineered antibody also disabled a variety of related coronaviruses.When given to mice, it stopped SARS-CoV-2 from reproducing in the rodents’ lungs and protected the animals from respiratory disease.

Experiments showed that ADG-2 targets receptors found on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 and a range of similar coronaviruses. The authors dub this receptor the Achilles heel of coronaviruses closely related to SARS-CoV-2, and suggest that this vulnerability could be exploited to make vaccines against emerging coronaviruses.

28 January — The workers who keep us fed face some of the highest COVID risk

The death risk for essential workers in some sectors was 20–40% higher than expected during the first 8 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to an analysis of death records in California.

Yea-Hung Chen and his colleagues at the University of California, San Francisco, analysed state data for people aged 18–65 to estimate how many more deaths occurred among working-age adults during the pandemic than would have been expected without the onslaught of SARS-CoV-2 (Y.-H. Chen et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/frx9; 2021). The team found that compared with a no-pandemic scenario, deaths were 39% higher for food and agriculture workers, 28% higher for transportation and logistics workers and only 11% higher for non-essential workers.

The workers with the highest COVID-related risk included cooks, bakers, agricultural labourers and people who pack and prepare goods for shipment. Risk also varied by race and ethnicity: compared with the no-pandemic scenario, mortality during the pandemic was 36% higher for people aged 18–65 of Latin American descent overall and 59% higher for food and farm workers in this group.

The authors say essential workers should receive free personal protective equipment and easy access to testing. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

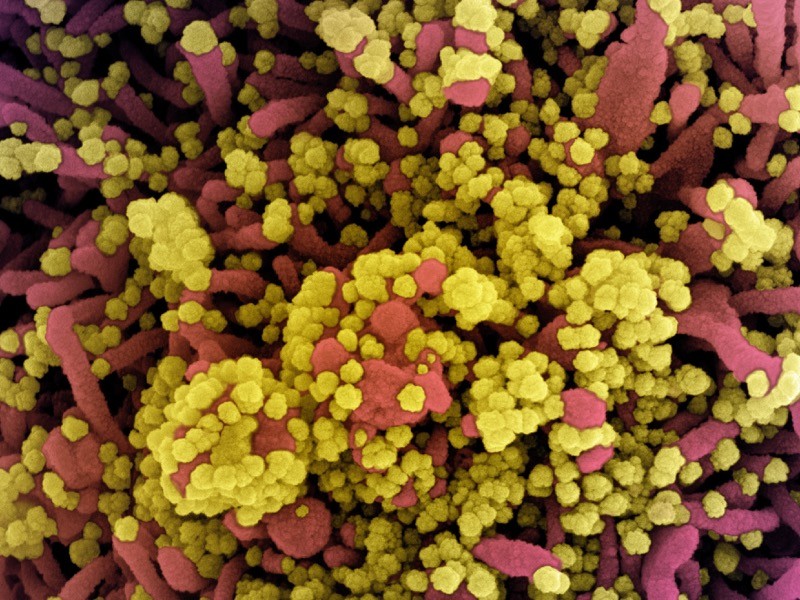

26 January — Moderna vaccine vanquishes viral variants

A leading COVID-19 vaccine seems to work against new, rapidly spreading variants of SARS-CoV-2.

Darin Edwards at biotechnology company Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and his colleagues collected blood samples from 8 people and 24 macaques that had received 2 doses of the company’s vaccine (K. Wu et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/fr2g; 2021). The vaccine instructs the body to make the coronavirus’s spike protein, priming the immune system to produce ‘neutralizing’ antibodies that can prevent cells from being infected. All of the blood samples from vaccinated people and monkeys contained neutralizing antibodies against the virus.

The researchers exposed the blood to viral particles that mimic a range of coronavirus variants, including an emerging form first found in the United Kingdom and another, 501Y.V2, first detected in South Africa. The samples’ neutralizing antibodies were as effective against the variant first found in the United Kingdom as against an older form of the virus, but only about one-fifth to one-tenth as effective at neutralizing 501YV.2. Even so, the antibodies were effective enough to provide protection against both variants, the authors say.

Moderna says it plans to test a booster to enhance immunity to emerging coronavirus variants. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

21 January — COVID vaccines might lose potency against new viral variants

Newly emerging, fast-spreading variants of the coronavirus might reduce the protective effects of two leading vaccines.

Michel Nussenzweig at the Rockefeller University in New York City and his colleagues analysed blood from 20 volunteers who received two doses of either the vaccine developed by Moderna or that developed by Pfizer–BioNTech (Z. Wang et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/frdn; 2021). Both vaccines carry RNA instructions that prompt human cells to make the spike protein that the virus uses to infect cells. This causes the body to generate immune molecules called antibodies that recognize the spike protein.

Within 3–14 weeks after the second jab, the study participants developed several types of antibody, including some that can block SARS-CoV-2 from infecting cells. Some of these neutralizing antibodies were as effective against viruses carrying certain mutations in the spike protein as they were against widespread forms of the virus. But some were only one-third as effective at blocking the mutated variants.

Some of the mutations that the team tested have been seen in coronavirus variants that were first identified in the United Kingdom, Brazil and South Africa; at least one of these variants is more easily transmitted than other forms of the virus now in wide circulation.

The findings suggest that vaccine-resistant variants might emerge, meaning that COVID-19 vaccines could need an update. They have not yet been peer reviewed.

Correction 28 January 2021: An earlier version of this article gave an incorrect time window for antibody development after vaccination.

20 January — The unsung viral feature that could lead to more COVID treatments

A usually overlooked region of a key SARS-CoV-2 protein is an important chink in the virus’s armour.

Neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 block particles of the virus, which makes them some of the body’s most potent weapons against the new pathogen. Most of the neutralizing antibodies that researchers have studied target a region of the virus’s spike protein called the receptor-binding domain (RBD). But previous studies have also identified neutralizing antibodies that act against other portions of spike — particularly a region called the N-terminal domain (NTD).

David Veesler at the University of Washington in Seattle and his colleagues analysed the blood of people who had recovered from COVID-19, and identified 41 antibodies that recognize the NTD (M. McCallum et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/fq92; 2021). Some proved to be as potent at blocking infection as were antibodies that recognize the RBD. Hamsters treated with one of the strongest NTD-targeting antibodies were protected from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Worryingly, the authors found that variants of the coronavirus first identified in the United Kingdom and South Africa carry mutations that might weaken the effects of some NTD antibodies. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

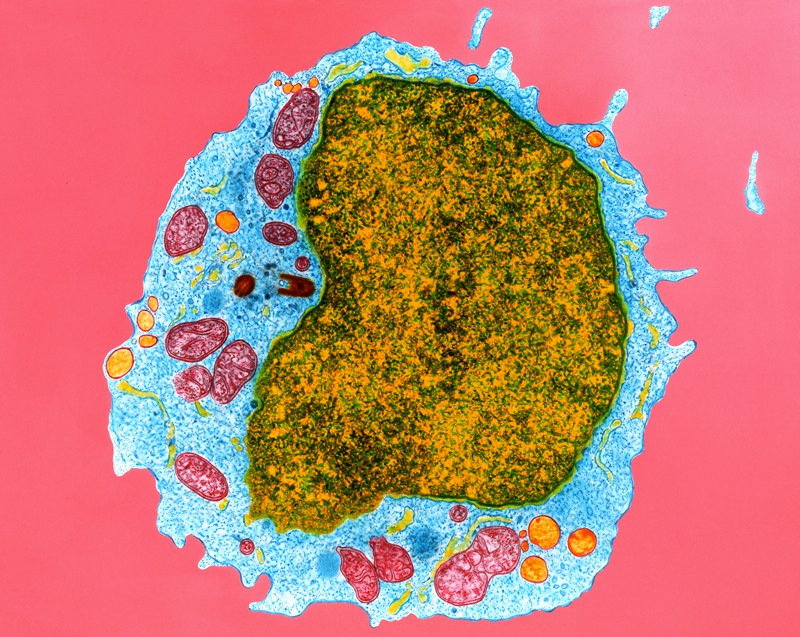

19 January — Immune cells ‘remember’ COVID for at least half a year

The immune system remembers how to make antibodies that can fend off the new coronavirus for at least six months after the initial infection.

Levels of antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 often wane in the months following infection, which has raised concerns that immunity to the virus declines rapidly. Michel Nussenzweig at the Rockefeller University in New York City and his colleagues collected blood samples from 87 people about 1 month and 6 months after they were infected with the virus (C. Gaebler et al. Nature https://doi.org/fq6k; 2021). The team monitored participants’ levels of antibodies and memory B cells, immune cells that would stimulate the production of antibodies against the virus if the study participants were reinfected.

The team found that levels of antibodies against the coronavirus’s spike protein declined over six months. But participants’ levels of memory B cells specific for making antibodies against the spike protein remained constant. The researchers sampled the intestines of 14 participants 4 months after infection and found that half had persistent SARS-CoV-2 protein or RNA, potentially providing a continued source of stimulation to the immune system.

15 January — Two anti-inflammatory drugs prevent COVID deaths

Two drugs that dampen the body’s immune response can save the lives of people with severe COVID-19.

Some people gravely ill with COVID-19 have tissue damage inflicted by their own immune response, and also show increased activity of immune-system molecules and cells regulated by a protein called IL-6. To study the effect of quashing IL-6 activity, Anthony Gordon of Imperial College London and his colleagues tested the drugs tocilizumab and sarilumab, which block the protein that immune cells use to detect IL-6 (A. C. Gordon et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fqgf; 2021).

The team gave the drugs to 803 adults with COVID-19 who were in intensive care and receiving organ support, such as ventilation or high-flow oxygen. Of these participants, 353 received tocilizumab, 48 received sarilumab and 402 received neither. The drug treatment reduced the death rate — from nearly 36% in the control group to 28% among those who received tocilizumab and 22% for sarilumab.

The results have not yet been peer reviewed.

14 January — A potential COVID vaccine causes a durable immune response

A candidate vaccine spurs both younger and older people to make antibodies against the coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, according to early trial results.

The vaccine, which is under development by Johnson & Johnson, headquartered in New Brunswick, New Jersey, uses a harmless virus to inject cells with the instructions for making the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Hanneke Schuitemaker at Janssen Vaccines and Prevention in Leiden, the Netherlands, and her colleagues tested the vaccine’s safety and immune-stimulating properties in more than 800 people aged 18 years and up (J. Sadoff et al. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/fqnt; 2021).

Almost 100% of study participants aged 18–55 years had developed potent antibodies against the virus 57 days after receiving a single low dose of the jab. In a separate arm of the trial, the same regimen triggered the development of antibodies in 96% of participants aged 65 years and older 29 days after vaccination. Side effects were largely mild or moderate, and antibodies persisted until at least 71 days after inoculation.

The results of larger efficacy trials of the vaccine are pending.

13 January — A mutation undercuts the immune response to the COVID virus

A handful of mutations to SARS-CoV-2 can help it to escape the immune response mounted by a subset of infected people.

Researchers have identified thousands of mutations in SARS-CoV-2 samples, but the vast majority are unlikely to have much effect on the virus’s biology. To identify potentially important mutations, Jesse Bloom at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues studied antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 isolated from the blood serum of people who had recovered from COVID-19 (A. J. Greaney et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/ghr85d; 2021).

The team tested the antibodies’ response to samples of the virus’s spike protein. Each sample protein carried different versions of a region called the receptor binding domain (RBD), which recognizes host cells and is a major target for antibodies.

Of thousands of RBD mutations tested, only a few reduced the antibodies’ ability to bind tightly to the spike protein — a change that might also indicate a reduction in the antibodies’ ability to disable the virus.

But the effects varied substantially between people. The most consequential mutations, at a location called E484, caused a steep drop in the potency of some individuals’ antibodies. Coronavirus variants identified in South Africa and Brazil carry a mutation at the same spot.

The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

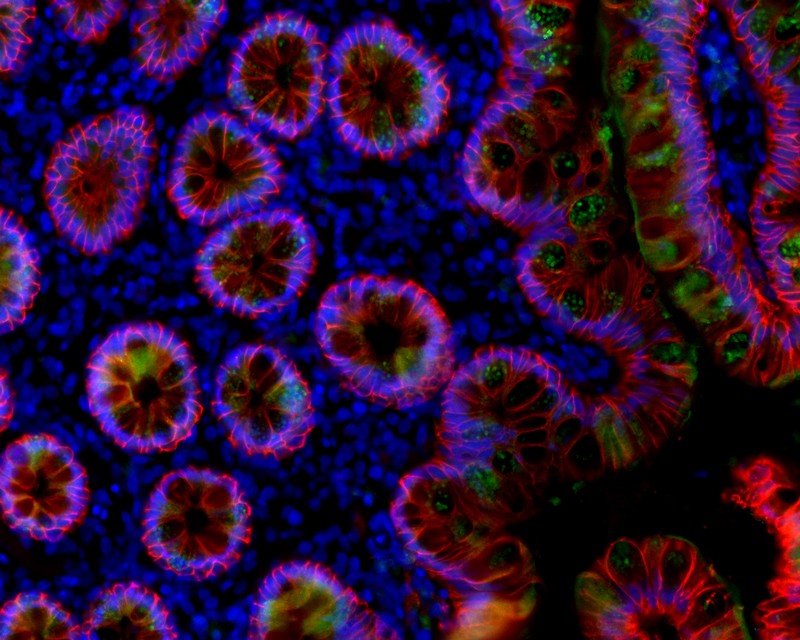

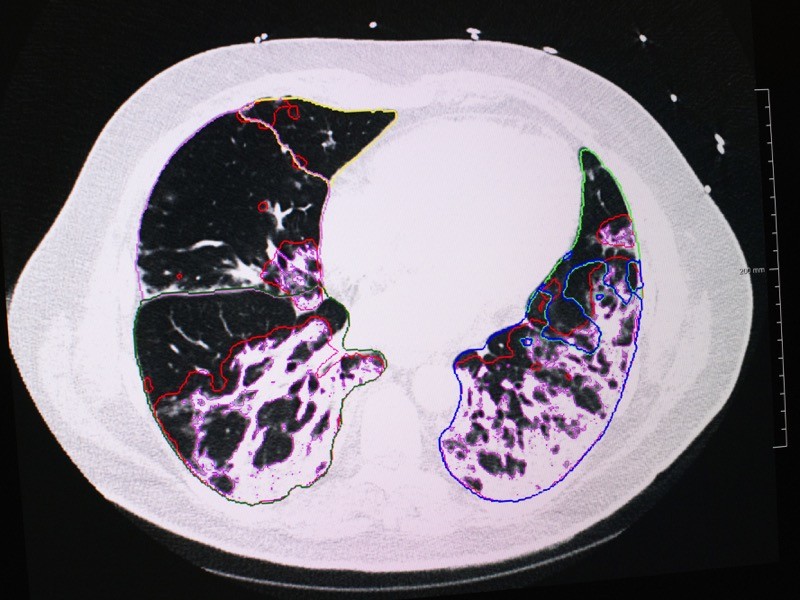

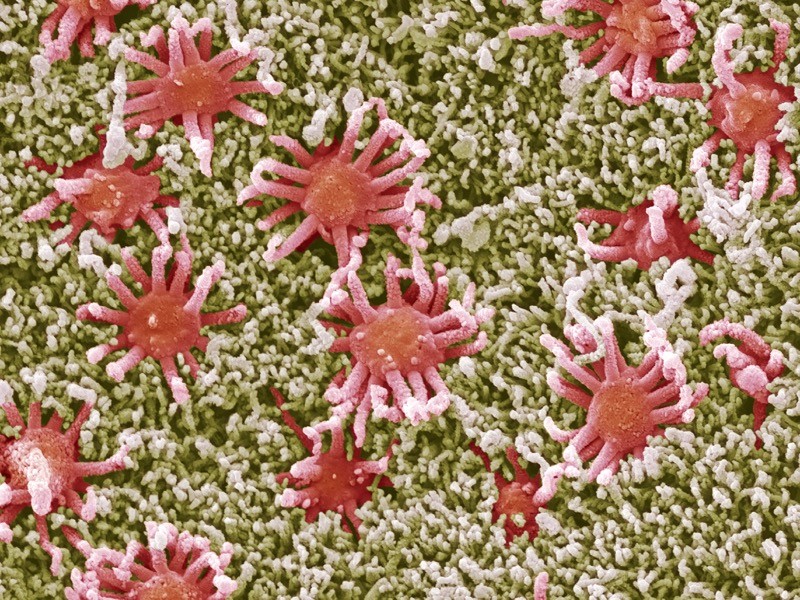

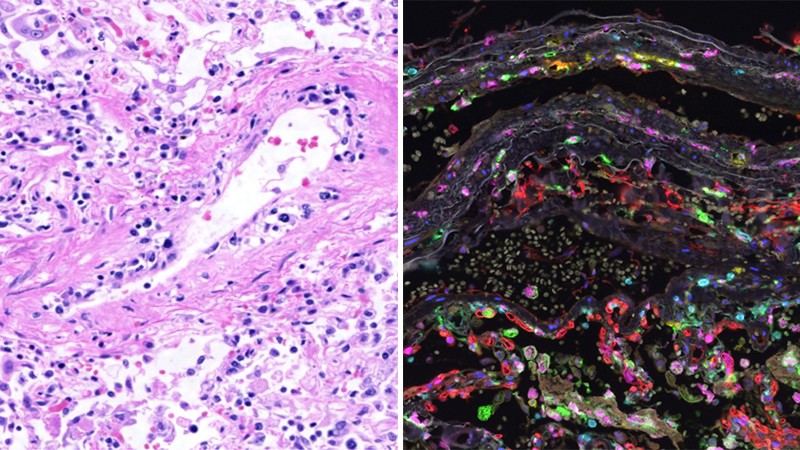

12 January — Immune cells gone wild are tied to COVID lung damage

Some of the severe respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 seem to result from the activity of specific immune cells, which can cause long-term inflammation of the lungs.

Alexander Misharin at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, and his colleagues examined fluid from the lungs of 88 people with severe pneumonia caused by SARS-CoV-2 infection (R. A. Grant et al. Nature https://doi.org/fqds; 2021). Most of these individuals had high numbers of a certain type of T cell, a class of immune cells, in their lungs. The researchers also found that nearly 70% of alveolar macrophages, a type of immune cell that is located in the tiny air sacs of the lungs, contained SARS-CoV-2. The cells harbouring the virus showed relatively high expression of genes involved in inflammation.

The findings suggest that, once the virus reaches the lungs, it can infect macrophages, which respond by producing inflammatory molecules that attract T cells. T cells, in turn, produce a protein that stimulates macrophages to make more inflammatory molecules. This persistent lung inflammation could lead to some of the life-threatening consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

11 January — Traitorous antibodies are linked to COVID death

Antibodies normally attack pathogens, but, sometimes, rogue antibodies instead besiege bodily components such as immune cells. Now, a new study adds to the growing body of research tying these ‘autoantibodies’ to poor outcomes in people with COVID-19.

Ana Rodriguez and David Lee at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine in New York City and their colleagues studied autoantibody levels in blood serum collected from 86 people who required hospitalization for COVID-19. The researchers were particularly interested in autoantibodies against the protein annexin A2, which helps to stabilize cell-membrane structure. It also plays a part in ensuring the integrity of tiny blood vessels in the lungs. Blocking annexin A2 leads to lung injury, a hallmark of COVID-19.

The scientists found that the level of anti-annexin A2 antibodies was, on average, higher in the individuals who eventually died of COVID-19 than in those who survived — a difference that was statistically significant (M. Zuniga et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fqdd; 2021).

More research is necessary to establish a clear causal link between the virus SARS-CoV-2 and autoantibodies against annexin A2, which are relatively rare. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

8 January — Quick treatment with antibody-laden blood cuts risk of severe COVID

A clinical trial in older adults with COVID-19 shows that an early dose of blood plasma from recovered people helps to prevent the progression to severe disease.

The plasma of people who have recovered from COVID-19 contains antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. But treatment with such plasma has had mixed results, and some scientists have suggested that plasma needs to be given early in the disease course to be effective. Fernando Polack at Fundación INFANT in Buenos Aires and his colleagues conducted a rigorous clinical trial to assess the effect of treatment with plasma within 72 hours of symptom onset. Participants included people over the age of 75 and those between 65 and 74 with at least one pre-existing condition such as diabetes (R. Libster et al. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2033700; 2021).

Severe COVID-19 developed in 16% of the 80 study participants who received plasma and 31% of the 80 participants in the placebo group. The team found that donor plasma containing higher concentrations of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 was associated with a greater reduction in the risk of developing severe disease — providing evidence that the antibodies themselves are responsible for the therapeutic effect.

7 January — Evidence grows of a new coronavirus variant’s swift spread

Two independent analyses have found that a new SARS-CoV-2 variant overtaking the United Kingdom is indeed more transmissible than other forms of the virus.

Eric Volz and Neil Ferguson at Imperial College London and their colleagues examined nearly 2,000 genomes of the variant, which has been labelled variant of concern 202012/01. The genomes were collected in the United Kingdom between October and early December 2020. The team also analysed the results of roughly 275,000 UK COVID-19 tests administered in late 2020 (E. Volz et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ghrqv8; 2021).

Estimating the variant’s frequency over time, the authors concluded that it is roughly 50% more transmissible than other variants. The authors also found that a UK lockdown in November curbed COVID-19 cases caused by most viral variants — but cases linked to the new variant rose. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

A separate team also used genomic and other data to analyse the variant’s spread in the last few months of 2020. Nicholas Davies and his colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine estimated that the new variant is 56% more transmissible than other variants (N. Davies et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fp3v; 2020). The authors found no evidence that the variant of concern causes more severe COVID-19 than other variants. The findings are now under peer review.

6 January — A less-sensitive COVID test could help to curb outbreaks

Rapid COVID-19 tests that trade away a degree of reliability for speed could prove a valuable public-health tool in communities that are hit hard by the disease.

In one week, Diane Havlir at the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues tested about 3,300 people in the city for SARS-CoV-2 (G. Pilarowski et al. Clin. Inf. Dis. https://doi.org/fpzv; 2020). All the study volunteers had two tests: the gold-standard PCR test, which typically returns results in two to four days in the United States; and a rapid test that detects viral proteins called antigens and returned results in roughly one hour. The rapid test, BinaxNOW, is made by Abbott Laboratories in Abbott Park, Illinois.

The rapid test detected 89% of the 237 people who tested positive with PCR — and it detected all of those who had high levels of the virus. Within two hours of a positive rapid-test result, participants received a phone call advising them to isolate themselves. This swift response meant people were less likely to spread the infection than they might have been had they waited for a PCR result. Approximately 1% of the positive rapid antigen tests were not confirmed by PCR — meaning they were wrong.

Study author Havlir disclosed that she receives non-financial support from Abbott that is not related to the paper.

4 January ― A vaccine works quickly to ward off COVID-19

An RNA-based vaccine recently approved by US regulators can provide protection against COVID-19 within two weeks of the first dose, according to the results of a large clinical trial.

On 18 December, the US Food and Drug Administration granted an emergency-use authorization to a vaccine made by Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Shortly thereafter, Lindsey Baden at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, Hana El Sahly at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas, and their colleagues published the results of a vaccine trial that enrolled more than 30,000 volunteers. Half received two doses of a placebo and half received two doses of the vaccine, 28 days apart (L. R. Baden et al. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/ghrg8m; 2020).

The vaccine was 94% effective at preventing symptomatic COVID-19, and preliminary analysis hints that just one dose of the vaccine might also provide some defence against asymptomatic disease, the authors write. All 30 trial participants who developed severe COVID-19 were in the placebo arm.

About half of volunteers who received the vaccine experienced side effects such as headaches after their second dose. But serious side effects were rare and occurred as frequently in the placebo group as in the vaccinated group.

21 December — How 90% of French COVID cases evaded detection

In the weeks after France ended its first lockdown, nine residents with COVID-19 symptoms went undetected for every person confirmed to have the disease — despite a nationwide surveillance programme.

France reopened in May but adopted a strategy of testing, contact tracing and case isolation to keep the coronavirus in check. To assess the results, Vittoria Colizza at the Pierre Louis Institute of Epidemiology and Public Health in Paris and her colleagues modelled COVID-19 transmission in France between mid-May and late June. They found that the national testing campaign missed some 90,000 people with COVID-19 who showed symptoms at a time when infections in the country were declining (G. Pullano et al. Nature https://doi.org/fn9k; 2020).

The findings show that a low rate of positive test results does not always equate to a high rate of detected cases. The results also suggest that many people with symptoms of COVID-19 did not seek medical advice or testing.

Countries need to implement more aggressive and efficient testing of people with suspected infections if surveillance is to be a useful tool for fighting the pandemic, the researchers say.

18 December — Stay-at-home orders have limited value for curbing COVID

An analysis of COVID-19 data from 41 countries has identified 3 measures that each substantially cut viral transmission: school and university closures, restricting gatherings to no more than 10 people and shutting businesses. But adding stay-at-home orders to those actions brought only marginal benefit.

Questions linger about the relative effectiveness of specific measures to reduce the spread of SARS-CoV-2. To pinpoint the most useful, Jan Brauner at the University of Oxford, UK, and his colleagues modelled the number of new SARS-CoV-2 infections in 41 countries between 22 January and either 30 May or the first easing of restrictions (J. M. Brauner et al. Science https://doi.org/ghp2p7; 2020). The team also examined when each country implemented seven common anti-transmission measures.

By combining the two data sets, the researchers found that closing schools and universities had a “large effect” in dampening viral spread. Most countries closed schools and universities in quick succession, making it impossible for the team to disentangle the effects of each type of closure.

In countries that closed schools and businesses and restricted gatherings, a stay-at-home order did little more to reduce transmission, the authors found.

16 December — Self-sabotaging antibodies are linked to severe COVID

Antibodies usually fight off infection, but occasionally the immune system makes some that erroneously attack the body’s own organs and even the immune system itself. New results show that these ‘autoantibodies’ might explain why some people have a severe reaction to infection with SARS-CoV-2.

Akiko Iwasaki and Aaron Ring at the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and their colleagues studied 194 people with COVID-19 and found that the most seriously ill had high levels of autoantibody activity (E. Y. Wang et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fnkt; 2020). Some of the autoantibodies attacked the body’s immune cells, hampering the ability to fight off infection. Others attacked the central nervous system, the heart, the liver or connective tissue.

No single autoantibody was common enough to be used to distinguish people with COVID-19 from uninfected people. The authors say the diversity of autoantibodies could explain the various disease states that follow COVID-19.

14 December — A drug duo that helps people with severe COVID

A combination of the drugs baricitinib and remdesivir shaved one day off the recovery of people hospitalized with COVID-19.

The US National Institutes of Health recommends remdesivir as a treatment for some people with COVID-19. But questions linger about remdesivir’s effectiveness, and the World Health Organization cautions against its use.

To test it as part of a combination therapy, Andre Kalil at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha and his colleagues gave remdesivir and the anti-inflammatory drug baricitinib to roughly 500 people hospitalized with moderate or severe COVID-19 (A. C. Kalil et al. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/ghpbd2; 2020). Some 500 people in a control group received remdesivir and a placebo. The team monitored how long it took participants to recover enough to go without sustained medical care.

Those who took both drugs had a median time to recovery of seven days, compared with eight days for those who took only remdesivir. But for people who were on the edge of requiring invasive ventilation, median recovery time fell from 18 days on remdesivir alone to 10 days on both drugs.

11 December — How to save the most lives when a COVID vaccine is scarce

Front-line health-care workers will probably be the first to get COVID-19 vaccines, but who should be next in the queue when supplies are limited? Models suggest that it should be elderly people.

Kate Bubar and Daniel Larremore at the University of Colorado Boulder and their colleagues modelled the effects of rolling out a vaccine if various age groups are given priority (K. M. Bubar et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ghj6xw; 2020). The researchers also examined the influence of the rate of viral spread in the population, the speed of vaccine delivery and the effectiveness of the protection offered by the vaccine.

The team found that in most scenarios, giving the jabs to people older than 60 before those in other age groups saved the greatest number of lives. But to prevent as many people as possible from getting infected, countries should prioritize younger age groups, according to the analysis.

Targeting people who have not been infected with SARS-CoV-2 to receive the vaccine might cut deaths and infections in hard-hit regions further, the researchers say. This could be achieved by testing for antibodies against SARS-CoV-2, which indicates a history of recent infection. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

8 December — A coronavirus vaccine shows lasting benefit

People given a front-runner COVID-19 vaccine still had high levels of potent antibodies against the coronavirus four months after their first jab.

Biotech firm Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has reported that its vaccine is more than 94% effective at preventing COVID-19. To gauge whether this protection lasts, Alicia Widge at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Bethesda, Maryland, and her colleagues analysed blood from 34 study volunteers who received two doses of the vaccine one month apart (A. T. Widge et al. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/ghnhnv; 2020).

The volunteers’ levels of antibodies that latch on to a key SARS-CoV-2 protein peaked 1–2 weeks after the second jab and fell only slightly in the subsequent 2.5 months. Four months after the first jab, their blood still contained ‘neutralizing’ antibodies that disable the virus, and none of the participants had experienced any serious vaccine-related side effects.

The results show that the vaccine could provide a “durable” antibody response, the authors write.

7 December — Just a pinch of antibodies can protect against COVID

Low levels of antibodies to the new coronavirus might be sufficient to protect against COVID-19, according to a study of infected monkeys. The study also found that immune cells called T cells contribute to immunity to the virus, particularly when antibody levels are low.

There is no easy way to predict which aspects of an immune response will provide protection against an infectious disease. Dan Barouch at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues sought to understand which immune elements defend against COVID-19 using rhesus macaques (Macaca multatta).

The team collected antibodies from macaques that were recovering from SARS-CoV-2 infection and gave the antibodies to uninfected macaques (K. McMahan et al. Nature https://doi.org/fmjk; 2020). The antibodies protected the recipient animals from infection and boosted a host of immune responses, including the activation of antibody-dependent natural killer cells. Higher doses of antibodies conferred greater protection than did lower doses.

When the researchers reduced the recovering macaques’ levels of CD8+ T cells, the animals’ immunity to re-infection fell. This suggests that these cells also contribute to coronavirus immunity.

4 December — Smell tests could sniff out rising COVID case counts

A fast, cheap test of a person’s ability to smell could help to stop COVID-19 outbreaks, according to models.

Previous studies have reported that more than three-quarters of people infected with SARS-CoV-2 lose some or all of their sense of smell — a statistic that holds true even for those who do not feel ill. This distinctive symptom prompted Roy Parker at the University of Colorado Boulder and his colleagues to model whether mass testing for loss of smell could help to quash an epidemic (D. B. Larremore et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fmbb; 2020).

The team’s simulations showed that a smell test administered every three days could prevent a spike in infections in a population of 20,000 people, assuming that at least 50% of infected people experienced a detectable loss of smell. The tests would also be effective for surveillance before mass events such as aeroplane flights, the modelling showed.

Study author Daniel Larremore disclosed that he advises test company Darwin Biosciences; author Derek Toomre disclosed that he is a founder of smell-test company u-Smell-it. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

3 December — The mutations that let the coronavirus give antibodies the slip

Scientists have identified a SARS-CoV-2 mutation that allows the virus to escape recognition by several antibodies manufactured as COVID-19 treatments.

The designer therapies called monoclonal antibodies are modelled on naturally occurring immune molecules. Jesse Bloom at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, Washington, and his colleagues mapped every possible SARS-CoV-2 mutation that could prevent binding by three monoclonal antibodies: one manufactured by Eli Lilly in Indianapolis, Indiana, and the two in a ‘cocktail’ made by Regeneron in Tarrytown, New York (T. N. Starr et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/fk6h; 2020).

The mutations affect a protein segment called the receptor-binding domain, which the virus uses to bind to and enter cells. The researchers found one mutation that caused the virus to escape recognition by Regeneron’s antibody cocktail, and a few others that helped it to escape one of the three antibodies.

Few of these mutations are circulating widely in infected people. But one is prevalent in Europe, and another has been detected in the Netherlands and Denmark, where it has been found in SARS-CoV-2 samples taken from mink and people working at mink farms. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

2 December ― Why a sensitive COVID test can yield false negatives

The gold-standard method for diagnosing COVID-19 is the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test, which detects the coronavirus’s genetic material in a nose or throat swab. Now, a survey of more than 15,000 people has singled out the people most likely to receive false negatives on the test.

Caitlin Dugdale at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston and her colleagues looked at PCR test results from about 15,000 people who showed COVID-19 symptoms or were thought for other reasons to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 (C. M. Dugdale et al. Open Forum Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/fkw4; 2020). Nearly 2,700 individuals tested negative and had a second PCR test done within 2 weeks.

Among those who received a second test, 60 — or 2.2% — tested positive. Of these, 60% had their initial test either one day or less before symptom onset or more than 7 days after it, suggesting that the PCR test is most likely to yield a false negative in people tested early or late in the course of infection.

People with COVID-19 symptoms who test negative should be retested, especially in areas where the virus is widespread, the researchers say.

1 December — To avoid COVID, beware your nearest and dearest

A far-reaching study of SARS-CoV-2 transmission in China’s Hunan Province found that the encounters that were most likely to spread the coronavirus were those between members of the same household.

Kaiyuan Sun at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland, Hongjie Yu at Fudan University in Shanghai, China, and their colleagues analysed data from 1,178 people in Hunan who were infected with SARS-CoV-2 and more than 15,000 close contacts of the infected people (K. Sun et al. Science https://doi.org/fkwm; 2020). The team found that contacts between people who live together posed the greatest risk of transmission, followed by contacts between members of an extended family. The transmission risk was lower still for social contacts and community encounters, such as those on public transport. Every extra day of contact raised transmission risk by 10%, the team found.

The analysis suggests that Hunan’s lockdown actually increased the risk of viral spread within households, whose members spent more time than normal at home together during lockdown. But social and community transmission fell during the same period.

20 November — Immune responses to coronavirus persist beyond 6 months

The immune system’s memory of the new coronavirus lingers for at least six months in most people.

Sporadic accounts of coronavirus reinfection and reports of rapidly declining antibody levels have raised concerns that immunity to SARS-CoV-2 could dwindle within weeks of recovery from infection. Shane Crotty at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California and his colleagues analysed markers of the immune response in blood samples from 185 people who had a range of COVID-19 symptoms; 41 study participants were followed for at least 6 months (J. M. Dan et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/ghkc5k; 2020).

The team found that participants’ immune responses varied widely. But several components of immune memory of SARS-CoV-2 tended to persist for at least 6 months. Among the persistent immune defenders were memory B cells, which jump-start antibody production when a pathogen is re-encountered, and two important classes of T cell: memory CD4+ and memory CD8+ T cells. The results have not yet been peer-reviewed.

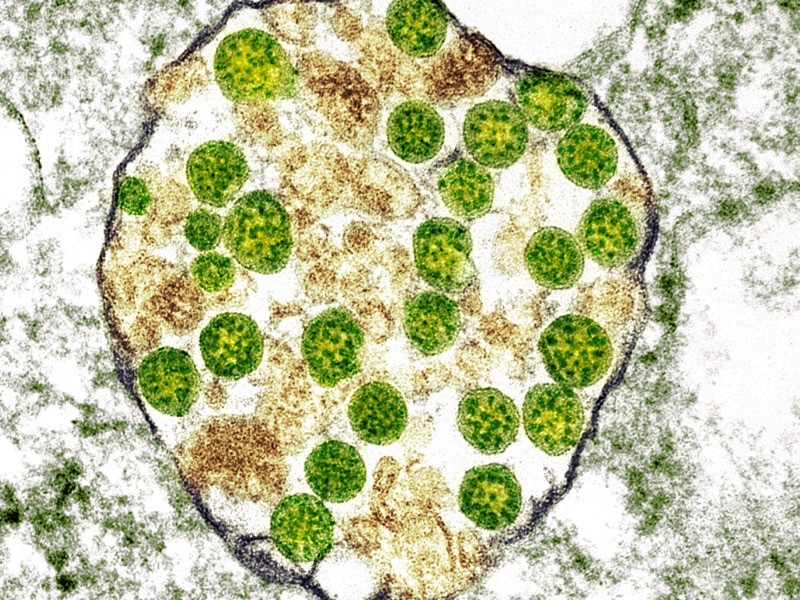

19 November — The coronavirus mutates rapidly as it races through mink farms

The coronavirus is adapting to its mink hosts, suggests a genetic analysis of farmed animals infected with SARS-CoV-2.

Outbreaks of coronavirus have been reported on farms breeding mink (Neovison vison and Mustela lutreola) across Europe and the United States since April. François Balloux at University College London and his colleagues studied 239 viral genomes isolated from farmed animals in the Netherlands and Denmark (L. van Dorp et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/fjj6; 2020).

The team identified at least seven separate instances in which the virus had jumped from people infected with SARS-CoV-2 to mink. The researchers also found 23 mutations that had arisen independently at least twice, suggesting that the virus was rapidly adapting to its new host.

Some of these frequent mutations appeared in regions of the genome that encode the spike protein that coronaviruses use to infect cells. But researchers say there is no evidence that these changes in mink will affect SARS-CoV-2’s ability to spread in people if it jumps back to humans. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

17 November — Colds caused by coronaviruses might not ward off COVID

Although SARS-CoV-2 can be deadly, it has mild-mannered cousins called seasonal coronaviruses that are among the causes of the common cold. Some scientists have suggested that people might be shielded from SARS-CoV-2 infection if they have recently been infected by a seasonal coronavirus.

Scott Hensley at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and his colleagues examined blood samples collected before the pandemic from some 500 people (E. M. Anderson et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fh2n; 2020). The team found that all of the study participants had pre-pandemic antibodies that could recognize the seasonal coronavirus OC43. One-quarter of participants also had antibodies that could recognize SARS-CoV-2, which probably developed in response to infection with a common-cold coronavirus.

Half of the participants went on to catch SARS-CoV-2. Individuals who became infected and those who didn’t had similar levels of antibodies recognizing SARS-CoV-2. This suggests that neither those antibodies nor those that recognize OC43 offer protection against infection, the authors say.

17 November — Quick COVID tests catch the people who are most infectious

Rapid antigen tests for the coronavirus are faster, cheaper and more user-friendly than standard diagnostic assays. An assessment now shows that some antigen tests — but not all — can tell with high accuracy who is likely to be most infectious.

Antigen-based assays detect specific proteins, or antigens, on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 particles. Christian Drosten at the Charité — University Hospital Berlin and his colleagues analysed the performance of seven commercially available rapid antigen tests. The researchers applied the tests to a range of samples, including dozens of swabs from people who had already tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 or for other respiratory viruses using the gold-standard polymerase chain reaction test (V. M. Corman et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ghj3wt; 2020).

The five most sensitive antigen assays detected the presence of SARS-CoV-2 on 95% of the test runs for samples with concentrations of viral genetic material that ranged between the equivalent of 3.4 million and 74 million copies per millilitre of swab. Such high viral levels are observed during the first week of symptoms, when people are likely to spread the virus to others. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

13 November — The coronavirus can mutate swiftly in one person’s body

The new coronavirus resurged again and again in the body of an infected man, eventually killing him while showing evidence of fast-paced evolution.

Manuela Cernadas and Jonathan Li at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, and their colleagues followed the course of COVID-19 in a 45-year-old man with a long-standing autoimmune disorder, who was on a medication regimen that included powerful immunosuppressants (B. Choi et al. N. Engl. J. Med. https://doi.org/fhv8; 2020). Roughly 40 days after the man first tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, follow-up tests indicated that the virus was dwindling — but it surged back, despite antiviral treatment.

The man’s infection subsided and then returned twice more before he died, five months after his first COVID-19 diagnosis. Genomic analysis showed that the man had not been infected multiple times. Instead, the virus had lingered and quickly mutated in his body.

12 November — The mystery of one African nation’s low COVID death toll

One of the first large SARS-CoV-2 antibody studies in Africa suggests that by mid-2020, the virus had infected 4% of people in Kenya — a surprisingly high figure in view of Kenya’s small number of COVID deaths.

The presence of antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 indicates a history of infection with the virus. Sophie Uyoga at the KEMRI-Wellcome Trust Research Programme in Kifili, Kenya, and her colleagues searched for such antibodies in samples of blood donated in Kenya between late April and mid-June (S. Uyoga et al. Science https://doi.org/fhsx; 2020). Based on those samples, the researchers estimate that 4.3% of Kenya’s people had a history of SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The team’s estimate of antibody prevalence in Kenya is similar to an earlier estimate for the level in Spain. But Spain had lost more than 28,000 people to COVID-19 by early July, whereas Kenya had lost 341 by the end of the same month. The authors write that the “sharp contrast” between Kenya’s antibody prevalence and its COVID-19 deaths hints that the coronavirus’s effects are dampened in Africa.

11 November — A coronavirus mutation could weaken antibodies’ power

A widespread variant of the new coronavirus has the potential to evade the immune response that some people mount after infection.

Since the start of the pandemic, researchers have identified thousands of viral mutations in the genomes of SARS-CoV-2 samples taken from infected people. David Robertson at the University of Glasgow, UK, Gyorgy Snell at Vir Biotechnology in San Francisco, California, and their colleagues examined a mutation called N439K in a protein that the virus uses to invade cells (E. C. Thomson et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/fhnp; 2020).

The mutation affects the protein’s receptor binding domain, which it uses to recognize host cells, and which is a key target of antibodies against the virus. The mutation has emerged independently at least twice and has been identified in 12 countries.

In laboratory experiments, the researchers found that the mutation could hinder the activity of potent neutralizing antibodies that block the virus. Among the neutralizing antibodies that the mutation obstructed were those in the blood of people who had recovered from COVID-19, as well as some manufactured ‘monoclonal antibodies’ that are being developed into treatments. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

9 November — Uninfected children have antibodies to the coronavirus

Scientists have found antibodies that recognize SARS-CoV-2 in the blood of people who have never caught the virus. Children are particularly likely to harbour such antibodies, which might explain why most infected children have either mild illness or none at all.

It has been unclear whether previous infection with one of the ‘seasonal’ coronaviruses — which cause the common cold — wards off SARS-CoV-2 or its severe symptoms. George Kassiotis at the Francis Crick Institute in London and his colleagues analysed blood samples from both adults and children who had not been infected with the new virus (K. W. Ng et al. Science https://doi.org/fg9k; 2020). The samples were collected either before the pandemic began or just as the virus began its global march.

The team found that roughly 5% of 302 uninfected adult participants had antibodies that recognize SARS-CoV-2. So did more than 60% of uninfected participants aged 6 to 16 — the age group in which antibodies to seasonal coronaviruses are most common. Most blood samples from uninfected people who had antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 blocked the new coronavirus from infecting cells in lab dishes.

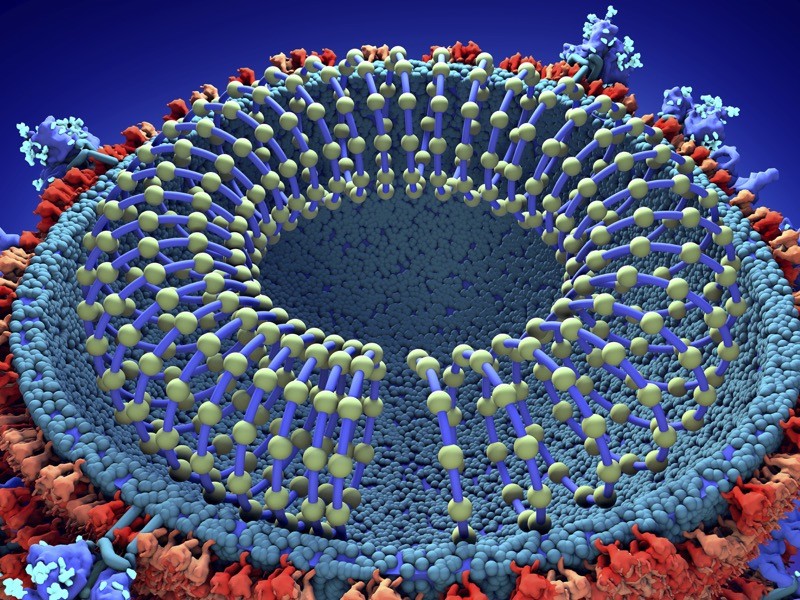

6 November — A vaccine that mimics the coronavirus prompts potent antibodies

A COVID-19 vaccine candidate made of tiny artificial particles could be more powerful than other leading varieties at triggering a protective immune response.

David Veesler and Neil King at the University of Washington in Seattle and their colleagues designed microscopic ball-shaped particles that mimic the structure of a virus (A. C. Walls et al. Cell https://doi.org/fg6r; 2020). The researchers fused 60 copies of SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein — the part of the virus that allows it to infect human cells — to the outside of each of these ‘nanoparticles’.

When the team injected mice with the nanoparticle vaccine, the animals produced virus-blocking antibodies at levels comparable to or greater than those produced by people who had recovered from COVID-19. Mice that received the vaccine produced about ten times more of these antibodies than did rodents vaccinated only with the spike protein, on which many COVID-19 vaccine candidates rely.

The vaccine also appears to produce a strong response from special immune cells that help to mount a fast defence after infection with SARS-CoV-2.

4 November — Many surfaces carry coronavirus RNA — but not much of it

Swabbing of bank machines, shop-door handles and other frequently touched surfaces in a US city revealed that 8% of samples were positive for SARS-CoV-2 genetic material, but that material was present in small amounts.

Amy Pickering at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts, and her colleagues repeatedly sampled 33 surfaces in public places in Somerville, Massachusetts (A. P. Harvey et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/fgx9; 2020). The handles of a rubbish bin and a liquor store were the most frequently riddled with coronavirus RNA. All samples showed only “low-level” contamination, and the infection risk from touching one of the contaminated surfaces is low, the researchers say.

The team found that the percentage of positive samples in one postal district peaked roughly 7 days before a spike in COVID-19 cases in the same district. Sampling of heavily touched surfaces might provide a warning of a surge of infections, the authors write. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

2 November — The coronavirus’s spread in households is fast and often silent

The new coronavirus spreads more efficiently in US homes than previous research suggested,sometimes without any symptoms to warn of its transmission, according to intensive monitoring of more than 100 US households.

Melissa Rolfes at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues recruited 101 US residents who had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 and had recently developed COVID-19 symptoms (C. G. Grijalva et al. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. https://doi.org/fgx3; 2020). For at least a week after enrolment, the researchers gathered daily coronavirus test results from 191 people who lived with the infected people.

For a conservative estimate of disease spread, the researchers excluded contacts who tested positive when their household signed up for the study. All the same, 35% of the remaining participants eventually tested positive — almost double one previous estimate. Fewer than one half of household contacts who became infected showed symptoms when they first tested positive, and 75% tested positive five days or less after the first infected person in their home began feeling ill.

2 November — How 45 countries rank on coronavirus infections

A country’s tally of COVID-19 deaths among those aged under 65 can be used to reveal the total number of people who have been infected.

Megan O’Driscoll at the University of Cambridge, UK, and her colleagues compared data on COVID-19 deaths across 45 countries (M. O’Driscoll et al. Nature https://doi.org/fgts; 2020). The researchers found that among people younger than 65, the risk of dying of COVID-19 increased with age in a pattern that was consistent across all countries.

The team also compiled statistics from 22 studies in 16 countries on the percentage of people who had SARS-CoV-2 antibodies, which indicate that they have previously been exposed to the virus. This helped the authors to estimate the infection fatality rate, which is the proportion of people who die after being infected with SARS-CoV-2, for the 45 study countries.

The researchers combined the infection fatality rates and the under-65 death statistics to estimate that by the beginning of September, some 5% of the 3.4 billion people in the 45 countries studied had been infected with SARS-CoV-2. South Korea had the lowest infection rate, at just 0.06%, and Peru had the highest with 62%.

This method could be used to estimate how many people have been infected in areas that cannot carry out large antibody surveys, the researchers say.

30 October — Coronavirus-fighting antibodies linger for months

The body’s antibody defence against the coronavirus remains strong for at least three months after infection, according to a study of more than 100 people who mostly had mild to moderate COVID-19.

Ania Wajnberg at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City and her colleagues analysed blood samples from more than 30,000 people who had been infected with SARS-CoV-2 (A. Wajnberg et al. Science https://doi.org/fgfs; 2020). More than 90% of the infected people had moderate or high levels of antibodies in their blood, and experiments showed that these antibodies could block the virus from infecting cells.

The team also re-tested a subset of 121 individuals at two later dates and found that their antibody levels were stable for at least three months. Five months after symptom onset, the individuals’ antibodies showed only a modest decline . The authors say that it is “very likely” that the antibodies shield people from re-infection.

28 October — A fur-farm animal can spread the coronavirus

The small fox-like animals called raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) can be infected with SARS-CoV-2, and can spread it among themselves.

Conrad Freuling at the Friedrich Loeffler Institute in Greifswald–Isle of Riems, Germany, and his colleagues deliberately infected nine raccoon dogs with the new coronavirus (C. M. Freuling et al. Emerg. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/ffzf; 2020). Six began shedding the virus from their noses and throats several days later. When three uninfected animals were put in cages next to the infected animals, two got infected. None of the animals became visibly sick, but some were slightly lethargic.

These findings suggest that SARS-CoV-2 could spread undetected in fur farms in China, where more than 14 million raccoon dogs live in captivity. The coronavirus that caused the pandemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2002–2004 was also isolated in raccoon dogs, and could have first jumped to people from the canids.

27 October — Basketball stars score with coronavirus insights

Professional basketball players in the United States have helped to provide details of a poorly understood phase of SARS-CoV-2’s life cycle: its behaviour in the bodies of newly infected people.

After a four-month hiatus, US basketball games resumed in July. Before and after play restarted, athletes and staff members were repeatedly checked for SARS-CoV-2 with a version of the highly sensitive polymerase chain reaction method, which can be used to assess a person’s viral levels. The intensive testing offered a rare chance to monitor viral levels in infected people who had not yet developed symptoms, and in those who never felt ill.

Stephen Kissler at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues analysed test results from 68 people involved in the season (S. M. Kissler et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/ffxk; 2020). Study participants’ viral levels peaked about three days after they tested positive. The researchers found that two tests given within two days can indicate whether a person’s viral level is rising or falling — information that can influence treatment decisions. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

26 October — A maths-based strategy streamlines COVID testing

In ‘pooled’ testing for SARS-CoV-2, samples from multiple people are combined into one batch that is then analysed for the virus. Now, a large-scale trial has shown that pooled testing can be highly efficient — even more so than theory predicted.