You have full access to this article via your institution.

The UK government has given the green light to another runway at London Gatwick Airport, as part of its mission to boost growth.Credit: Henry Nicholls/AFP/Getty

Last week’s United Nations General Assembly, held in New York City, generated no shortage of headlines. But one notable policy initiative from the world body was not discussed by world leaders when it should have been. UN secretary-general António Guterres has put together a high-level group of specialists to propose new indicators for human and planetary prosperity that go ‘Beyond GDP’. The intention is to accelerate progress towards achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and researchers are being invited to contribute. When the working group publishes its recommendations next year, its advice could have far-reaching consequences. That is why we are urging researchers the world over to engage.

GDP is getting a makeover — what it means for economies, health and the planet

Guterres’ project is called Beyond GDP because of the necessity of getting past the world’s go-to indicator of economic progress: gross domestic product (GDP). It is the sum of what consumers spend, what governments and businesses spend and invest as well as the net value of exports and imports. Over its 70-year lifespan, GDP growth has become the benchmark for national economic competence. Every country’s leader and their finance teams do what they can to ensure that GDP data only ever point upwards.

And yet, for decades, researchers have been pointing out that this approach creates perverse incentives and could be creating as many problems as it solves — particularly when growth in GDP undermines other aspirations encapsulated in the SDGs. GDP fetishism, as economist Joseph Stiglitz, of Columbia University in New York City, calls it, is one reason why the SDGs are a long way from being achieved before their 2030 target deadline.

The tensions are already apparent in the wording of SDG 8, which deals with economic growth. It commits countries to “promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth”. For sustained growth, governments often reach for tried-and-tested ideas, such as loosening regulations to build more roads or expand airports — giving less thought as to whether that growth is inclusive or undermines sustainability goals such as SDG 12 (responsible consumption and production) and SDG 13 (climate action). Because GDP is the emperor of all indicators, everything else becomes subordinate to it.

That is what makes the work of the UN-appointed group so important. The 14-member panel, co-chaired by economists Kaushik Basu at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, and Nora Lustig at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, is deliberating on a broad set of indicators, each of which should have equal weight to GDP. It is an extremely ambitious undertaking — and exceptionally complex.

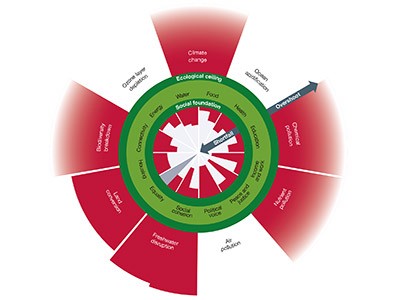

Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries monitors a world out of balance

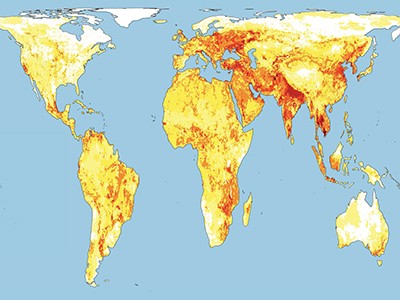

Exactly how complex is set out in a paper in Nature this week1. Economists Andrew Fanning and Kate Raworth of the Doughnut Economics Action Lab in Oxford, UK, describe a set of 35 social and ecological indicators that attempts to provide some answers to the questions being examined by the panel. They report 13 ecological indicators that draw on the Planetary Boundaries framework, developed by environmental scientists. These are the numerical ‘boundaries’ for nine Earth-system processes — including air pollution, climate change and biodiversity loss — that regulate the Earth’s stability and resilience. Seven of the nine have been breached. They also measure 22 social indicators that connect specifically to other SDGs, including the number of undernourished people (in line with SDG 2: zero hunger), adults who cannot read or write (SDG 4: quality education) and those lacking access to safely managed water and sanitation (SDG 6: clean water and sanitation). Between 2000 and 2022, the researchers find that, whereas global GDP has more than doubled, “the increase in ecological overshoot would have to halt immediately” to safeguard Earth-system stability by 2050.

Read the paper: Safe and just Earth system boundaries

This work extends Raworth’s original idea of ‘a safe and just space for humanity’ (see go.nature.com/4mzgxgb), later published in the book Doughnut Economics (2017), in which she described the model of ecological and social boundaries. Raworth’s thinking grew out of the first study that described the Planetary Boundaries concept2. In 2023, for the first time, its authors updated their model to incorporate environmental justice — that people have rights to water, food, energy and health, alongside a clean environment3.

Over the years, economists, not least Stiglitz and fellow Nobel prizewinner Amartya Sen, have proposed replacing GDP with a constellation of alternatives4. Raworth and Fanning’s study updates this for the age of SDGs. Their indicator list, does not, however, include the conventional measures that go into GDP, such as spending and investment. This will probably be a source of debate and discussion among economists.

The latest study and the UN initiative are an opportunity for researchers across economics to engage with each other to achieve the best possible outcome for people and the planet. As Raworth wrote in Doughnut Economics: “We have economies that need to grow, whether or not they make us thrive; what we need are economies that make us thrive, whether or not they grow.”