“Mars is a failed Earth.” It is common enough to hear such perspectives expressed in reference to our planetary neighbour’s lack of Earth-like qualities, including a thick atmosphere, plate tectonics, oceans and a biosphere. As far as we know, the surface of Mars is hostile to and devoid of life — and so is most of outer space.

Now would be a good time to reconsider this attitude. We are at a pivotal moment in the history of space exploration. Over the past several decades, the search for extraterrestrial life has shifted from the idle anticipation of technologically advanced aliens contacting or visiting Earth to the active development of scientific missions that seek signs of such life, in the Solar System and beyond. Numerous ongoing and upcoming missions have been tasked with searching for signs of habitability and life in the cosmos1,2, presaging what could be a golden age of astrobiology — the study of alien life. Meanwhile, the rising influence of private space corporations is bringing human space flight into a new, commercially driven age. Using technologies developed by companies such as SpaceX and Blue Origin, US astronauts aim to head once more to the Moon as part of NASA’s Artemis programme, which could act as a stepping stone for missions to Mars and beyond. Other countries, including China, have similar ambitions, or might develop their own programmes.

Ethics in outer space: can we make interplanetary exploration just?

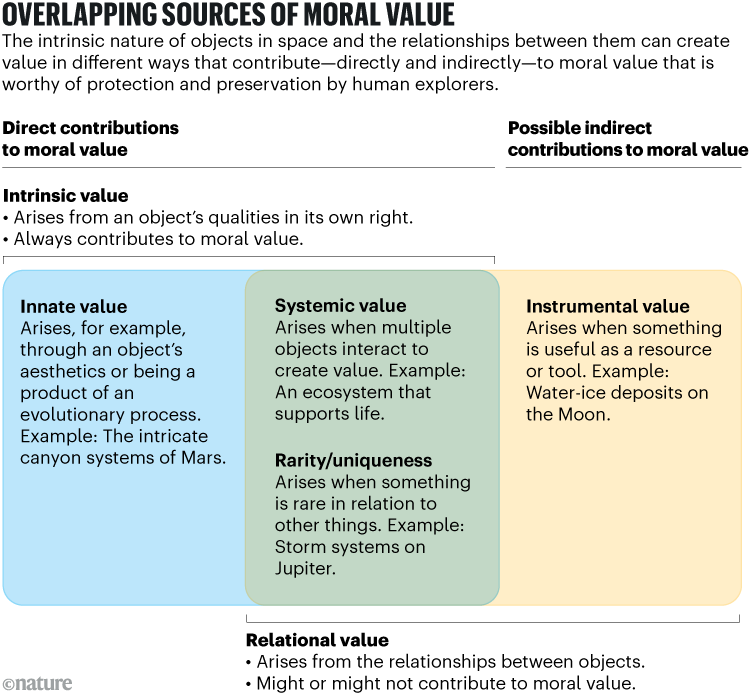

As human influence extends farther, broader ethical guidelines are needed for the exploration and treatment of extraterrestrial environments and phenomena. Rarely is any value ascribed to what space contains beyond the purely instrumental — how it furthers our knowledge of the cosmos or boosts human ambitions. Here, we argue that assessing what deserves our moral consideration in outer space requires a more expansive set of factors that can contribute to moral value than those that have generally been applied through our current, terrestrially based thinking. That, in turn, must inform how we set about exploring space — and preserving what we find there.

What is moral value?

As moral agents, humans have a general obligation to respect what is morally valuable. When considering questions about moral value, a distinction has conventionally been made between an object’s instrumental value (its worth as a means to an end for something else) and its intrinsic value (its value for its own sake). Most ethicists would say that objects that have only instrumental value do not have moral value. In this way of thinking, humans are generally considered hugely intrinsically valuable; our mere existence should be enough for us to feel obliged to treat each other well. By contrast, money is only instrumentally valuable, because its worth is derived solely from its use in human–human exchanges; it does not deserve moral consideration for its own sake. Objects can have multiple forms of value at once: a tree, for instance, might be considered intrinsically valuable as a living thing, but also instrumentally valuable as a source of food, oxygen, lumber and shade.

How to distinguish intrinsic value from instrumental value has been debated for millennia. In Western analytical philosophy (in contrast, it must be said, to many other conventions), an uncompromising ‘biocentric’ cut-off is sometimes imposed3: being alive is almost always a prerequisite for moral consideration. Within that boundary, many ethicists following the Western convention have taken a stratified approach, basing conditions for a moral consideration on mental attributes such as rationality, autonomy and sentience. Sentientism focuses on a being’s ability to experience certain types of welfare change that other entities can’t. For example, it is now widely acknowledged that lobsters can feel pain, spurring some countries to ban boiling them alive. By contrast, ratiocentrism proposes that only rational creatures — those with the capacity to act through reasoning rather than only on instinct — should be given moral consideration.

Even though it seems to be devoid of life, the rocky terrain of Mars contains much that might be worth preserving.Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Del-4Ri

Such accounts can reinforce a hierarchical view of intrinsic value, with humans either placed at the pinnacle or given preference. Some philosophers, for example, have argued4 that animals other than humans that are ‘sophisticated’ enough to participate in human society (such as dogs and horses) or to be social themselves (chimpanzees and bonobos, for instance) sit just below humans in this hierarchy. Beings that do not display signs of neurological sentience, such as plants and microorganisms, occupy the bottom rung.

This ‘life bias’5 in approaches to moral value has limitations when looking further afield. Our planet, with its abundance and diversity of life, is special in some ways, as far as we know. Outer space, by contrast, is devoid of life and of sentient, rational beings — or at least those parts of outer space that we are likely to explore on any reasonable timescale seem to be. But it is a leap in reasoning from seeing that Earth is special to concluding that only Earth is special, and that there is little, if anything, of moral value in outer space.

Why space exploration must not be left to a few powerful nations

We argue that a one-dimensional hierarchy of moral value misses the interconnected webs of nature’s generative forces. More-over, it fails to acknowledge that many entities — living and inanimate, sentient and non-sentient, rational and irrational — can express several forms of value at once. In the case of space exploration, it misses the important possibility that inanimate entities and extraterrestrial systems can have tremendous moral value; certainly, we have yet to see proof that they don’t.

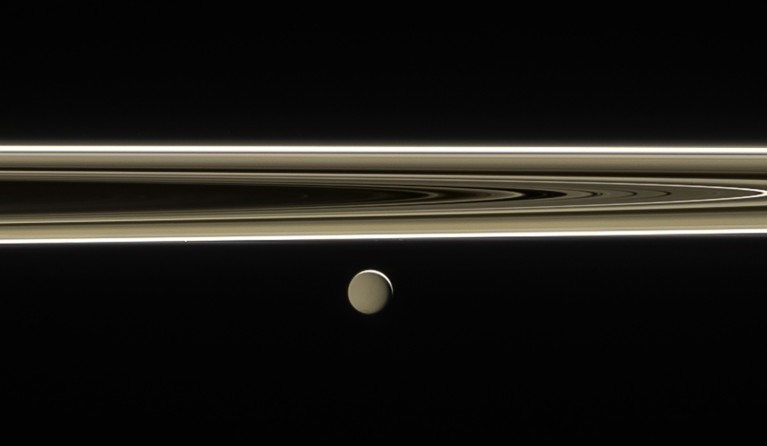

Similarly, although the instrumental value of outer-space environments to future human activities is widely acknowledged, focusing only on the distinction between intrinsic and instrumental value means we might miss or ignore other aspects that might contribute to moral value. For example, hydrothermal activity interacting with a hypothetical alien ecosystem on an ice-covered ocean world — say on Jupiter’s moon Europa or Saturn’s moon Enceladus — could generate a new kind of systemic value that ought to factor into ethical decisions regarding the exploration of such environments.

A new taxonomy of moral value

Our expanded taxonomy of moral value encompasses six overlapping and nested categories that can all contribute to an object’s overall moral value, in distinct ways and to various degrees. Intrinsic and instrumental values remain, but we augment them with the following categories: relational value, innate value, systemic value and rarity value (see ‘Overlapping sources of moral value’).

Source: C. Haramia et al.

Intrinsic value. This category remains defined essentially as the worth that objects have by dint of their own attributes. It has been noted6 that this can lead to varying delineations of the term’s precise meaning: as non-instrumental value; as value solely on the basis of an entity’s intrinsic properties, ignoring its relationships to anything else; or as an objective value possessed independently of any assessor. In this analysis, we take intrinsic value to encompass the first and third of these qualities: it is an objective property, independent of instrumental value.

Innate value. We define this type of value as a subset of intrinsic value. It is possessed by ostensibly discrete entities independently of any relationships to anything else, and so ticks all three boxes of the above-mentioned definitions of intrinsic value. Recognizing innate value begins with acknowledging the projective nature of the cosmos — how nature produces its own ‘projects’ through its incessant inventiveness and constructiveness7. Life, as a product of evolution, is an obvious example of this kind of value, but this projective integrity extends to inanimate entities, too. Take space environments such as Valles Marineris, Mars’s canyon system, which is the largest known in the Solar System; or the huge icy basin of Sputnik Planitia on Pluto and the cryovolcanic ‘tiger stripes’ on Enceladus. These phenomena can be regarded as innately valuable because of their aesthetic properties, their structural complexity or other factors. Everything we encounter in space is a product of cosmic evolution and therefore might, to some degree, have innate value. Our ethical considerations must acknowledge this.

Trump wants to put humans on Mars — here’s what scientists think

Relational value. This value is distinct from the intrinsic and innate ones. It encapsulates the value that can be produced by distinct entities through their interactions, such as those between an author and a reader, a child and a parent, a forest and its resident animals or a star and an orbiting planet. We contend that such relations can be morally valuable independently of the value status of the relation’s members. Most people would readily acknowledge that a relationship between two humans can produce value distinct from and not reducible to the value of the two individuals, who also exist in and of themselves. But the same is less obviously true for a whole host of other relations: the relationships between predator and prey that result in ecosystem stability; symbiotic ones, such as those between algae and fungi that create lichen; or the one between silicate weathering and the removal of atmospheric carbon dioxide on a terrestrial planet8. On Earth, such relations can also have instrumental value to humans, by creating the conditions that allow us to thrive.

Instrumental value. In our scheme, this is a subset of relational value: instrumentally valuable phenomena produce positive effects for the things or people they affect. We contend that instrumental value can be indirectly connected to moral value through its relations to things of intrinsic value. Lunar ice deposits possess instrumental value as a source of water (and, after hydrolysis, oxygen and rocket fuel) for crewed missions to the Moon and beyond; these resources could factor into moral considerations because they might contribute to the welfare of intrinsically valuable human explorers. Instrumental value is therefore relevant to questions about moral value when considering the real-world activity of astro-biological exploration and the interconnected possibilities of scientific searches.

The rings of Saturn and its moon Enceladus have great intrinsic aesthetic value — and perhaps other sources of moral value, too .Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/SSI/CICLOPS/Kevin M. Gill

Systemic value. This is generated when relational aspects factor into intrinsic value. It manifests in the systemic processes of entities interacting with each other and their environments. These are complex processes, not mere two-part relations. They have a kind of intrinsic value that cannot simply be reduced to a sum of the innate values of the system’s members, or even to what emerges from their distinct relations. Systemic value emerges when relationships have systemic integrity, generative or regenerative abilities, or an evolutionary potential. Ecosystems have systemic value, but so, too, can tightly interwoven inanimate processes8. Systemic value lies at the intersection of intrinsic and relational values, because it describes how dynamic systems comprising many interacting components can be valuable as a single entity and as a total that is greater than the sum of its parts.

Rarity value. This value, rating the uniqueness of an entity, is another way in which relational value can measured. For instance, a storm on Jupiter, a mountain on Mars or a human life are all rare, given the low occurrence of similar phenomena in the known Universe. The moral value this produces cannot be reduced to the entity’s innate nature, because innate value is considered independently of the value of other objects.