On 30 May, South Korea’s Supreme Court sent shockwaves through the academic community. It upheld a decision sentencing a prominent academic to two years in prison for sharing data of national importance with overseas researchers. The ruling has global repercussions.

While working at a leading university in South Korea, the academic, known as Professor Lee, had been collaborating with Chinese researchers as part of China’s Thousand Talents Plan (TTP), a government programme to recruit overseas experts. (Full names of parties and institutions are omitted here to preserve privacy, in accordance with South Korean law.) The technology Lee worked on — a remote-sensing system for autonomous vehicles known as light detection and ranging (LiDAR) — is designated as a ‘national core technology’ by the South Korean government. The court ruled that Lee had violated the South Korean Industrial Technology Protection Act by sharing national core technology, and had leaked trade secrets by sharing university-owned research data without consent or approval.

How I’m using AI tools to help universities maximize research impacts

This case is a wake-up call. As I know from my own studies on leaks of technological information, and my work with policymakers and industry leaders on strategies for safeguarding intellectual property, all scientists must be cautious and diligent in protecting data as borders dissipate in the digital age. Researchers should do more to reinforce research integrity and strengthen data protection. We must recognize that the data we handle are not just our own — but belong to our institutions, collaborators and the public, who fund and trust our work.

South Korea has tightened its approach to protecting technological assets in response to international legal disputes over intellectual property in the past decade. In 2014 and 2015, for example, two big cases were settled: Toshiba v. SK Hynix concerning computer memory chips, and Nippon Steel v. POSCO over steel-production technology. The South Korean businesses had to pay the equivalent of hundreds of millions of US dollars in civil damages.

Now, the government maintains a list of national core technologies, which includes for example semiconductors and active-matrix organic light-emitting diode displays. In March, the Korean Sentencing Commission, under the Supreme Court, increased the maximum punishment for overseas leakage of information about national core technologies to 12 years.

Cyberattacks are hitting research institutions — with devastating effects

Many researchers have not caught up. For example, Lee told the court that he did not think that the research materials his team was developing were national core technologies or trade secrets. As testified by a witness, the researchers’ work was still at the conceptual and patent-application stage. Information about them was shared in laboratory meetings and seminars. Some aspects were the subjects of filed patents or had been described in published papers.

The judges disagreed with Lee. They reasoned that, because the technological concepts around Lee’s research materials had been established or verified through experiments, their value as independent technologies could be acknowledged, and they could be developed into complete technologies through further research. This case implies that technologies officially designated and published as national core technologies by the South Korean government might be subject to the act’s penalties, even at early stages of research and development.

Lee’s crime was compounded by a further error — failing to declare the specific subject of his research under the TTP to his university. This aspect of the case is reminiscent of that of Charles Lieber, a chemist formerly at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who was convicted in 2021 for lying to US federal authorities about his ties to the TTP and Wuhan University of Technology in China, and for not paying taxes on his income from Wuhan.

Many scientists might find themselves collaborating with overseas partners without understanding the legal implications of doing so. What steps should researchers take?

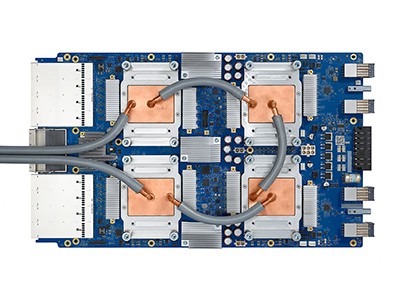

How cutting-edge computer chips are speeding up the AI revolution

First, universities need clear, explicit agreements for each international collaboration, specifying what data can be shared, with whom and how. Vague memoranda are no longer sufficient.

Second, researchers must undergo mandatory training on data security, export controls and intellectual property before embarking on international projects.

Third, research leaders must create a culture of responsibility. This requires normalizing practices such as labelling sensitive files, limiting access to data on a need-to-know basis and exposing risky behaviours. Researchers must be transparent with their institutions about involvement with overseas programmes and seek guidance early and often.

Fourth, governments and lawyers need to clarify what counts as a national core technology in research settings.

The stakes are high, and inaction is not an option. Failing to address these issues could lead to a chilling effect on international scientific collaboration, which would stifle innovation. By taking steps to protect sensitive data and foster responsible collaboration, researchers can ensure that global scientific cooperation continues to thrive, as well as safeguarding national interests and intellectual property.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.