Most governments’ astronomical borrowing throughout the present pandemic pays scant consideration to the results that climate change might have on their ability to repay the debt. Here we current an evaluation of nations’ sovereign debt issued in 2020, displaying that the overwhelming majority of countries didn’t disclose the methods wherein world warming may alter their credit-worthiness.

This is regarding. Even the anticipation of a climate shock may trigger a debt disaster. If monetary markets misprice the present danger, an occasion in a single nation might awaken buyers’ sensitivity, triggering a synchronized revaluation of sovereign debt all over the place.

This vulnerability may be prevented if climate dangers are correctly assessed and disclosed by governments which are issuing sovereign bonds to increase cash, and if the cash borrowed is spent on greening nations’ economies. As of early March 2021, round half of the COVID-19 stimulus funding that rich G20 nations had paid to the vitality sector — roughly US$250 billion — had gone in the direction of fossil fuels, moderately than to cleaner vitality sources (see go.nature.com/2qrratf).

Without extra transparency, buyers might demand a better rate of interest or refuse to lend completely. In February, BlackRock, one of many world’s largest asset-management corporations, set a “strategic preference” for developed markets, citing the chance of climate publicity in low- and middle-income nations and their extra carbon-intensive economies1.

As policymakers convene to focus on probably the most urgent financial challenges at this week’s Spring Meetings held by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, researchers and governments ought to take steps to obtain a climate-resilient restoration. This contains three approaches set out right here to keep away from COVID-19 lending that compounds the climate and debt disaster2. Countries ought to come clear about their climate publicity when taking up COVID-19 money owed. Pricing in these dangers would incentivize investments that would cut back the affect of climate change.

Sovereign debt

For centuries, governments have issued sovereign bonds (moderately like an IOU) to increase cash from home or worldwide buyers. This permits governments to spend on initiatives or insurance policies that improve financial productiveness, with out rising taxes within the brief time period. The rate of interest is about by the market to compensate buyers for the perceived danger concerned in lending to governments: the upper the chance of default, the upper the borrowing prices. That is why, in 2020, a 30-year bond from El Salvador, a lower-middle-income nation, was priced with an rate of interest of shut to 10%, whereas one from a secure high-income economic system reminiscent of Spain was nearer to 1%.

Judiciously borrowing cash to improve financial output can enable nations to earn a return that’s larger than their prices in servicing debt. As the economic system grows and tax receipts rise, governments can repay buyers and spend on public providers, reminiscent of well being care or schooling. For this motive, sovereign bonds had been probably the most important instrument within the debt capital markets earlier than the pandemic, accounting for practically half of the $115-trillion world bond market in 2019. During 2020, rich nations issued further bonds price tens of trillions of {dollars}, and rising economies issued lots of of billions’ price3.

Borrowing cash that doesn’t lead to financial progress may be damaging. An sudden shock to the economic system, reminiscent of COVID-19, can disrupt progress and make closely indebted nations susceptible to defaulting on their loans. Governments should then spend to service their money owed, moderately than put money into serving their residents. Alternatively, governments can borrow more cash, but when buyers anticipate elevated danger, they may cost a better rate of interest. The present pandemic poses a significant downside to the worldwide economic system. As of July 2020, a ‘debt tsunami’ of $130 billion was owed to collectors by greater than 100 low- and middle-income nations. Half of that is owed to personal lenders4. Development finance establishments, such because the World Bank and the IMF, have referred to as on authorities collectors to droop their debt-service obligations from the world’s poorest nations in gentle of the COVID-19 disaster (see go.nature.com/3cjyxwb). But personal holders of sovereign bonds are typically much less prepared to merely waive debt. The penalties may be extreme. In 2020, Zambia, Argentina, Belize, Ecuador, Lebanon and Suriname defaulted, with the end result that they now have troubled relationships with their collectors and may need to face austerity to handle repayments.

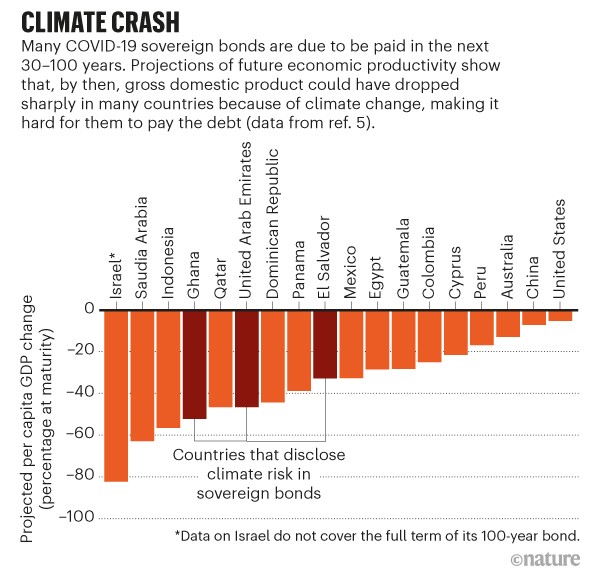

We analysed authorized paperwork governing private-sector lending to nations throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, and estimate that $783 billion has been borrowed via sovereign bonds that mature 30, 50 and even 100 years from now (see Supplementary Information, SI). During this timeframe, governments will both have to make investments to mitigate climate change as a part of their commitments below the Paris climate settlement — which might require a far-reaching decarbonization of the economic system — or face the prices of worldwide warming straight. Either means, this danger will have an effect on governments’ ability to repay or refinance excellent debt.

Climate change has the potential to severely have an effect on a rustic’s economic system. Over the 30–50-year interval lined by a lot of the COVID-19 lending, adjustments in world common temperatures alone could lead on to gross home product (GDP) falling by tens of proportion factors in some nations5. For occasion, when Saudi Arabia’s bonds mature in 2060, decrease productiveness within the nation might trigger its GDP to drop by 60% relative to eventualities with out climate change5 (see SI). These calculations are presumably conservative as a result of they exclude probably important impacts, reminiscent of more-intense and more-frequent excessive occasions6. When Hurricane Maria hit Dominica in 2017, it triggered injury price an estimated 220% of GDP. This left the federal government little room for spending aside from on restoration.

Undisclosed dangers

Our evaluation exhibits that 77% of the sovereign-bond prospectuses we reviewed didn’t disclose any climate-related dangers. We examined the publicly obtainable prospectuses of sovereign bonds and notes issued in 2020, which mature in or after 2050. This comprised 50 issuances from 26 nations (see ‘Climate crash’).

How ought to governments make such disclosures? The suggestions of the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD)7, which are actually broadly utilized by corporations, recommend that companies analyse two classes of danger and report them to monetary markets. One is bodily dangers, which take into account how projected adjustments within the climate will affect company productiveness. The different is transition dangers, which embody how climate-related adjustments in markets and authorities coverage will have an effect on the corporate’s asset values and techniques as nations transfer to lower-carbon economies. Although a country-specific framework for climate-risk reporting will differ from the corporation-focused TCFD suggestions, governments ought to nonetheless consider and report their bodily and transition danger exposures to debt markets.

We discovered that solely three governments (these of Bermuda, the Dominican Republic and El Salvador) acknowledged that more-frequent main climate occasions will create bodily dangers for his or her economies. Only two — these of Bulgaria and the United Arab Emirates — recognized the dangers of transitioning their economies to scale back emissions. And solely Ghana disclosed the impacts of each kinds of danger on its ability to repay.

Given the severity of those climate dangers, governments ought to assess and disclose them once they borrow cash. A financial institution will ask a buyer numerous questions earlier than giving them a mortgage, and can cost a better charge of curiosity if it thinks the person will battle to repay. Similarly, securities regulation and bond-listing guidelines in debt capital markets require governments to embody statements disclosing danger components that would undermine their ability to make repayments. These typically define the opportunity of regional geopolitical instability, wars and civil strife. Investors depend on these disclosures to assess whether or not the dangers are balanced by the returns (within the type of rates of interest) in lending to a rustic. This is especially essential when a authorities is concerned. If an investor loans cash to an organization, the investor often has authorized ‘sticks’ obtainable to guarantee they get their a reimbursement, together with an ability to seize the corporate’s belongings in the event that they default. But due to a authorized doctrine referred to as sovereign immunity, buyers can hardly ever seize the belongings of a authorities.

Even when climate-related disclosures had been made within the sovereign bonds, we discovered that the data offered was restricted. For occasion, Bermuda merely studies on the opportunity of main hurricanes and tropical cyclones occurring, and notes amongst others the 2019 Category 3 Hurricane Humberto, which triggered tens of thousands and thousands of {dollars}’ price of injury. Bulgaria’s prospectus discusses the affect of the European Union’s formidable net-zero emissions dedication on the nation’s coal business, on condition that “the country produced and processed approximately 7 per cent of the EU’s coal and represented approximately 7 per cent of the jobs in the EU’s coal sector in 2018”.

The gaps we discovered recommend that governments don’t perceive the financial impacts of climate dangers or are unwilling to report them. Both explanations are troubling, and will have important penalties for debt sustainability and climate coverage.

Flying blind

Without rigorous climate disclosures, buyers and governments are flying blind. The United Nations secretary-general warned in March that “we are on the verge of a debt crisis”. Evidence is mounting {that a} extreme future climate shock, reminiscent of a long-term drought in a rustic reliant on agriculture or the collapse of fossil-fuel industries, might trigger authorities defaults and a credit score disaster8. Revaluations in anticipation of such an occasion might additionally set off this.

Such an occasion could lead on to greater borrowing prices for susceptible governments, and even exclusion from business debt markets. It may also trigger buyers to withdraw from the nation, simply when it wants extra exterior capital to reply to the climate shock. This ‘capital flight’ can wreak havoc in low- and middle-income nations, as evidenced by the Latin American debt disaster of the 1980s. Future generations, notably within the poorest nations, might find yourself trapped in debt and poverty, aggravated by a warming world. Then it will be down to improvement finance establishments — and taxpayers within the rich nations that present them with capital — to avert humanitarian and financial catastrophe.

A revaluation of sovereign debt would hit probably the most susceptible nations the toughest. In the context of corporations, it would really be fascinating for buyers to redirect their capital away from the carbon-heavy industries of the previous and in the direction of the greener sectors of the long run. As funding shifts to new industries, it permits innovation and job creation so that individuals can observe. In truth, this rationale underpins a lot of inexperienced finance, in addition to many disclosure-based initiatives, such because the TCFD.

But such transitions have huge human and financial prices, notably for presidency debtors. Countries — not like corporations — can’t merely stop to exist when bankrupt. Instead, present and future residents will bear the price of debt burdens for generations. Moreover, lots of the poorest nations, which have contributed least to climate change, are these most uncovered to it. Better pricing of that danger would, by itself, solely increase the price of capital for these nations to finance decarbonizing and resilience-enhancing insurance policies.

For this motive, nations can have a powerful (short-term) disincentive in opposition to disclosing their climate danger exposures. However, as buyers more and more demand such disclosures as a situation for funding, and as nations face the prices of climate change, such a technique might expose governments to sudden will increase in borrowing prices. A gradual adjustment could be a lot much less disruptive. Yet it’s clear that higher disclosure of climate danger won’t be sufficient by itself to handle the challenges that low- and middle-income nations face.

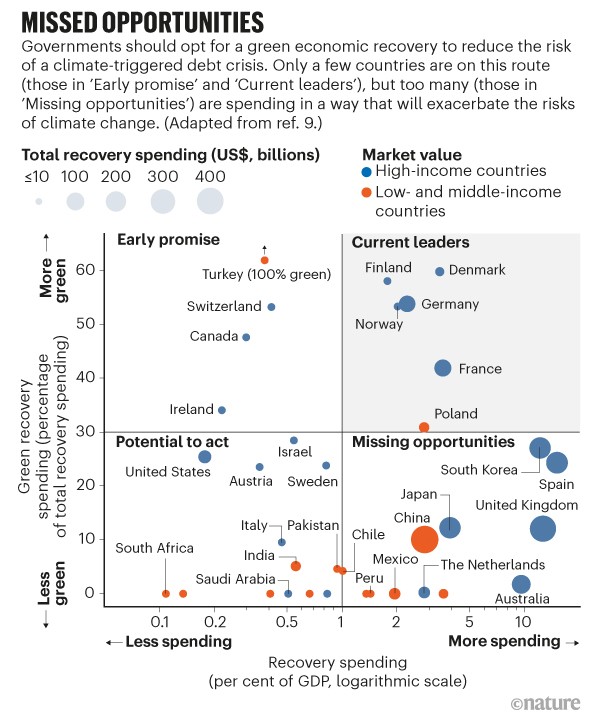

Wealthier nations should not incentivized to spend their COVID-19 restoration funds sensibly, as a result of their value of capital doesn’t mirror climate-change dangers. So far, solely 18% of complete introduced COVID-19 restoration spending is directed to actions that may scale back world emissions9. And long-term restoration spending is just 13% of the overall; most spending is for rescue moderately than restoration functions, and rescuing perpetuates the prevailing emissions-intensive world economic system. Despite calls to ‘build back better’, governments have financed actions which are damaging to the climate, together with a minimum of $6.9 billion on new coal infrastructure in India, and Germany’s $9.98-billion unconditional bailout of its main airline, Lufthansa10. Rather than creating prosperity and facilitating debt compensation, investing in outdated fossil-fuel applied sciences leaves future generations with extra money owed, greater value of capital, stranded belongings and even larger warming.

Together, these spending patterns might create a vicious cycle of COVID-19 debt, climate impacts and credit score dangers (see Supplementary Figure S1).

Three steps

Researchers, governments and monetary establishments ought to take three easy steps to treatment the scenario.

First, they have to work collectively to higher assess, disclose and handle vulnerability to sovereign climate danger. Part of the rationale climate danger is just not higher reported by governments and priced by buyers is that they don’t have the appropriate instruments. In a 2020 report11, worldwide monetary regulators and consultants wrote that governments want to make an “epistemological break” with their previous analytical strategies for forecasting financial danger, to cope with the non-linear and radically unsure nature of sovereign climate danger. Researchers ought to assist to develop these strategies, notably with respect to sovereign transition danger, and conduct country- and sector-specific analyses on how climate dangers are transmitted.

Key questions embody: how can higher eventualities be developed to consider socio-economic transitions? How quick might the construction of vitality manufacturing and costs change12? How will productiveness in numerous sectors be affected by adjustments in temperature? Modelling strategies want to be additional developed to reply these questions. These ought to account for uncertainty; the implications of aggregation, heterogeneity and distribution; and technological change. Most importantly, they need to embody practical injury capabilities for the financial affect of climate change13.

This large-scale endeavor may be achieved via small steps. Mandatory climate disclosures for corporations and asset managers, at the moment below means in lots of jurisdictions together with the EU, New Zealand and the United Kingdom, can kick-start the event of a broader info setting round climate dangers14. A standardized reporting framework tailor-made to nations moderately than corporations, comparable to the TCFD, could possibly be developed. Once that’s in place, inventory exchanges might replace itemizing steerage and standardized guidelines for climate danger disclosure in debt markets. Finally, to produce the required information and handle exposures, governments ought to enhance their coordination of climate and monetary coverage throughout departments. A broad group of presidency businesses will likely be wanted to account for climate danger, together with central banks, monetary regulators, finance and agriculture ministries and disaster-preparedness businesses all feeding into the advisory course of for debt administration.

Second, governments ought to use COVID-19 credit score to mitigate climate danger, construct climate resilience and broaden the economic system to support future debt compensation15. The Biden administration’s forthcoming restoration plan contains such a ‘build back better’ technique. Government spending on low cost clear vitality, for example, can scale back emissions, create jobs and stimulate financial progress. Every citizen ought to ask whether or not their nation’s COVID-19 restoration package deal is inexperienced sufficient. Some nations, together with South Korea, the United Kingdom and Australia, are lacking out (see ‘Missed opportunities’). There continues to be the potential to act, and governments within the United States, Canada, Switzerland and plenty of extra ought to seize this chance. The introduction of inexperienced sovereign bonds, which incentivize the borrower to use funds for inexperienced functions reminiscent of decreasing emissions, and the eye which credit score businesses pay to measuring resilience, recommend that bond markets will reward such efforts with decrease rates of interest.

Third, wealthier lender nations and their improvement finance establishments ought to present monetary help to probably the most susceptible borrower nations. The establishments should purchase again debt from closely indebted poorer nations, on the situation that the cash is used to improve climate resilience moderately than servicing the debt16. Debt-for-nature swaps have been used within the Seychelles, for example, with the UN Development Programme and different businesses decreasing the nation’s debt burden in trade for the federal government’s funding in climate resilience and biodiversity initiatives. Nature-performance bonds, which tie the price of debt repayments to quantified emissions-reductions targets or nature-based targets, characterize a extra versatile evolution of such swaps. These bonds might embody a wider vary of investments that may be readily scaled up, reminiscent of these for decarbonizing electrical energy manufacturing.

These three measures might assist governments to be sure that the credit score wanted to battle COVID-19 doesn’t exacerbate the climate disaster, leading to a credit score crunch for future generations. They can have sufficient to cope with.