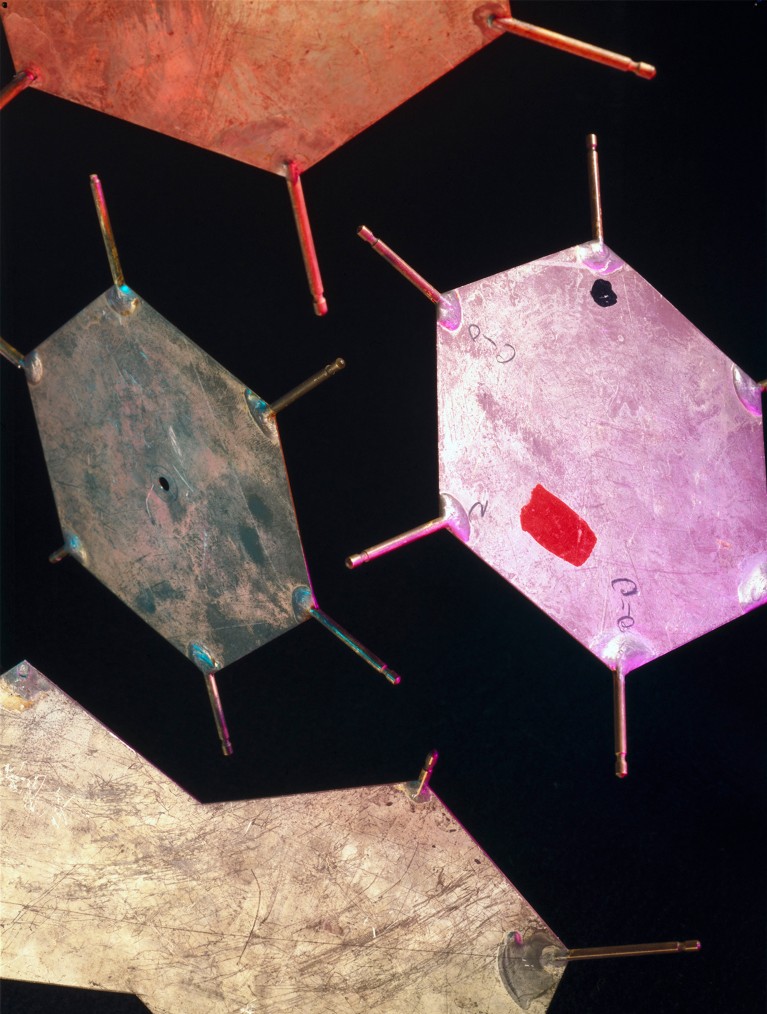

Francis Crick served in the British Admiralty and conducted research into naval mines.Credit: GL Archive/Alamy

Crick: A Mind in Motion — from DNA to the Brain Matthew Cobb Profile Books (2025)

Francis Crick has gone down in history as half of a double act with James Watson — a duo perhaps almost as iconic as the double-helix structure of DNA that they proposed. The pair were immortalized in Watson’s sensational 1968 book, The Double Helix, with Crick painted as garrulous and cerebral and Watson as gauche but driven. Watson had initially described his first draft as a novel, yet other published accounts of the discovery and the personalities involved have stuck closely to the script ever since.

In a magisterial new biography, Crick, zoologist and historian Matthew Cobb revisits the double-helix breakthrough, a discovery he discussed in forensic detail in his book Life’s Greatest Secret (2015). Yet, this time, the publication of the structure and the immediate aftermath of the discovery occupy just 41 pages. Instead, Cobb explores how Crick’s thinking, writing and interactions with others transcended that brilliant, yet contested, episode, revolutionizing molecular biology and influencing evolutionary and developmental biology, visual neuroscience and ideas about consciousness.

A new vision for how evolution works is long overdue

At the same time, he makes a more sustained attempt than either of Crick’s previous biographers (Matt Ridley and Robert Olby) to answer several questions. Who was Crick? What kind of person was he? What did he care about?

Crick was notoriously reluctant to divulge personal information or even have his photograph taken. Combing through a remarkably comprehensive set of personal and professional archives with meticulous attention to detail, Cobb has reconstructed Crick’s relationships with those who were essential crew mates on his intellectual odyssey.

Crick was born in 1916 in Northampton, a market town in the English Midlands, and grew up in a comfortable but not notably intellectual home. From an early age he had a burning desire to know why things were the way they were, a curiosity he satisfied by burying himself in the family copies of Arthur Mee’s eight-volume The Children’s Encyclopedia (1910). He did well enough at school to go to University College London to study physics, where he later began a PhD on the viscosity of water — “the dullest problem imaginable”, as Crick later said.

Richard Dawkins book of the dead is haunted by ghosts of past works

As Cobb explains, Crick’s future was transformed by his experiences during the Second World War. His PhD studies were interrupted when he was called up to serve in the British Admiralty, conducting research into naval mines — real-time problem-solving that suited his restless nature. In the Mine Design Department cafeteria he met Georg Kreisel, an Austrian refugee philosopher who had just graduated from the University of Cambridge, UK. Kreisel’s conversation and voluminous correspondence challenged Crick to sharpen his thinking and delighted him with their obscenities. Cobb makes the salacious letters part of the lifelong soundtrack to Crick’s intellectual endeavours.

Also working at the Admiralty was the “vivacious, talented and tolerant” artist Odile Speed. She became Crick’s second wife in 1949; their partnership was one of mutual devotion that allowed for his numerous affairs. Odile helped to develop his interest in art and literature, ran their households, hosted exuberant parties and raised their children. In short, she provided an environment in which Crick had the luxury of devoting all of his energy to his intellectual life.

Deciphering DNA’s code

In the late 1940s, disillusioned with physics and inspired by physicist Erwin Schrödinger’s 1944 book What is Life?, Crick decided that the nature of life was the only question worth pursuing, other than the neural basis of consciousness. He began a new PhD project in structural biology at the Medical Research Council’s Unit for Research on the Molecular Structure of Biological Systems — later known as the Laboratory of Molecular Biology — in Cambridge, UK, where he worked for almost 30 years. Under the genial chairmanship of molecular biologist Max Perutz, Crick never had to teach or grapple with university administration: he applied for a grant only once in his life. He had the grace to admit that luck had played a part in his success, but to some extent he made his own luck.

Cobb presents the double-helix story as much more of a collaboration with chemist Rosalind Franklin and biophysicist Maurice Wilkins at King’s College London than Crick and Watson acknowledged in their iconic 1953 paper (J. D. Watson and F. H. C. Crick Nature 171, 737–738; 1953). He exonerates Crick and Watson of theft, but not of bad manners. “They should have requested permission to use the data,” Cobb writes. “They did not.”

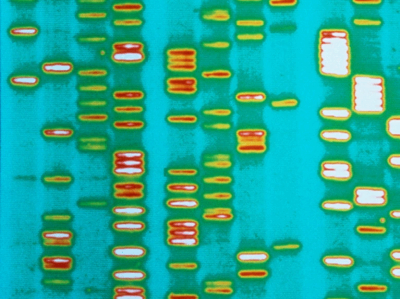

James Watson and Francis Crick co-discovered the structure of DNA.Credit: SSPL/Getty

The double-helix structure provided a springboard to understanding how information is transferred between DNA and the proteins it encodes. In Crick’s PhD thesis, he had called this the ‘central problem’ of biology. He tackled the issue with geneticist Sydney Brenner. Between them, they conceived the existence of messenger RNA, showed that the sequence of bases in mRNA acts as a code that dictates each protein’s amino-acid sequence and found that three bases encoded each amino acid (F. H. C. Crick et al. Nature 192, 1227–1232; 1961).

It’s time to admit that genes are not the blueprint for life