Lund University in Sweden is the subject of a study on the reporting of sexual harassment.Credit: Stigalenas/Getty

Sweden might rank among the top countries in the world in terms of gender equality, but a study from a major university has revealed that most sexual-harassment cases still go unreported in the country.

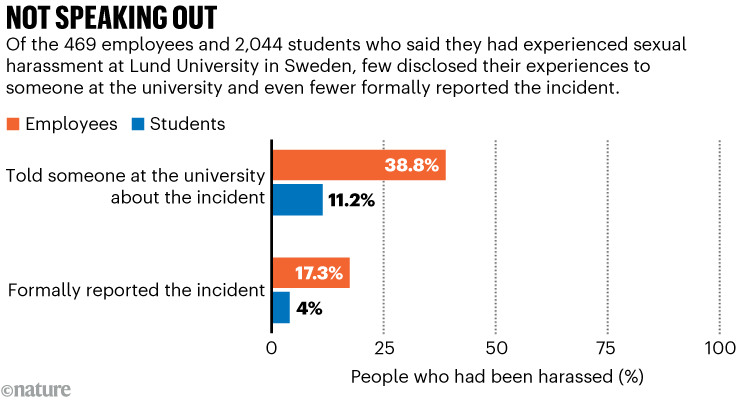

The study1, published in March in PLOS ONE, looked at answers to a general questionnaire sent out to all students and staff at Lund University. Responses came from around 2,700 employees, including PhD students, and almost 9,700 other students, such as those doing undergraduate and master’s degrees. Of the 469 employees who said they had experienced sexual harassment, only 38.8% disclosed their experiences to someone at the university, with a mere 17.3% reporting it formally. Among the 2,044 students who had been harassed, just 11.2% disclosed it and only 4.0% formally reported incidents (see ‘Not speaking out’).

I spent a year studying campus sexual violence. Here’s what I found out

Last year, Sweden came fifth in the Global Gender Gap Index, which scores countries on gender parity in areas such as economic participation, educational attainment, health and political empowerment. But that score doesn’t necessarily reflect a safer environment. The Lund findings echo those of a 2022 study2 of gender-based violence and sexual harassment in European research settings, which found that the prevalence of gender-based violence was fairly uniform across 15 nations.

“There are no model countries,” says Nicole Bedera, a sociologist in Minneapolis, Minnesota, who spent the 2018–19 academic year documenting how a US university handled sexual-assault allegations. “Even countries with a reputation of gender egalitarianism still tend to treat sexual-violence victims badly when they come forward.”

Age, experience, origin

The Lund survey included men, women and non-binary students and staff. The majority of both staff and students who said they had experienced sexual harassment were women, although gender did not significantly affect reporting rates. Other characteristics did have a role, however. University employees aged 40 years or younger were likelier to both disclose and formally report sexual harassment than were their older peers; students born outside Sweden were more likely to disclose and report than were those born in the country. (Birthplace had similar correlations among staff, although the difference was not large enough to be statistically significant.)

Source: Ref. 1

These students’ higher disclosure and reporting rates could mean that people not born in Sweden don’t have the same local social-support structures to help them cope with harassment events as do their Swedish-born peers, says Per-Olof Östergren, a social-medicine researcher at Lund University and lead author of the study. These individuals might also not be planning to stay in Sweden long-term and therefore might be less wary about the repercussions of reporting, he says.

But geographical origins also seem to correlate with sexual-harassment prevalence and reporting rates in subtle ways, he says. For instance, people born in Sweden were a little more likely to say they had experienced sexual harassment than were those born in other European countries. But it does not necessarily follow that Swedish-born employees and students are targeted more, he says. Rather, they could have a lower tolerance for harassing behaviour. “We will explore these trends in a forthcoming paper,” he says.

Higher professional rank was also linked with lower rates of disclosure and reporting. Although this was not a statistically significant finding, it was of concern to the authors, who in a 2022 study3 found that female professors and senior lecturers at the university experienced sexual harassment more often than other members of academic or technical staff. Sexual harassment of high-ranking women “could be interpreted as a way of punishing women who violate traditional constructions of femininity by taking on positions of power in the workplace”, they write now.

Enormous mechanism

The Lund study did not ask respondents why they did not disclose or report their experiences. However, another Swedish study from 2022 offers some insights. That work surveyed almost 40,000 students and staff members at Swedish higher-education institutions. Of those who said they had experienced sexual harassment, only 12% filed a formal complaint (14% of women and 8% of men). The most-cited reasons for keeping quiet were, for men, that “I dealt with it myself” and, for women, that “it wasn’t that serious”. “It would not have made a difference” was another common reason, cited by 42% of women and 23% of men.