On 31 March 2020, simply earlier than South Korea imposed a compulsory two-week self-quarantine for all incoming travellers amid the COVID-19 pandemic, Shik Shin, on the University of Tokyo, managed to ship one among his six laser photoelectron spectroscopes to the nation. The spectroscope is put in at a brand new laboratory at Seoul National University (SNU), collectively arrange in 2019 between his college’s Institute of Solid State Physics (ISSP) and the Center for Correlated Electrons Systems (CCES) of the Institute for Basic Science of Korea. Shin says the lab was established thanks primarily to his 20-year friendship with Se-Jung Oh, president of SNU, and different Korean collaborators on the CCES.

Since Shin pioneered ultra-high decision laser photoelectron spectroscopy in 2005, Japanese researchers have been utilizing the tools to uncover novel magnetic and superconducting properties of varied supplies that might result in the event of latest digital gadgets. He wished to introduce the tools to South Korea “because I felt something exciting will happen by combining both countries’ scientific strengths”, says Shin, who was elevated by the president of the University of Tokyo to the particular title of ‘university professor’ in physics on his retirement in 2019.

The ISSP and CCES, together with collaborators from Taiwan’s National Synchrotron Radiation Research Center, have held annual seminars in one among their three places since 2000.

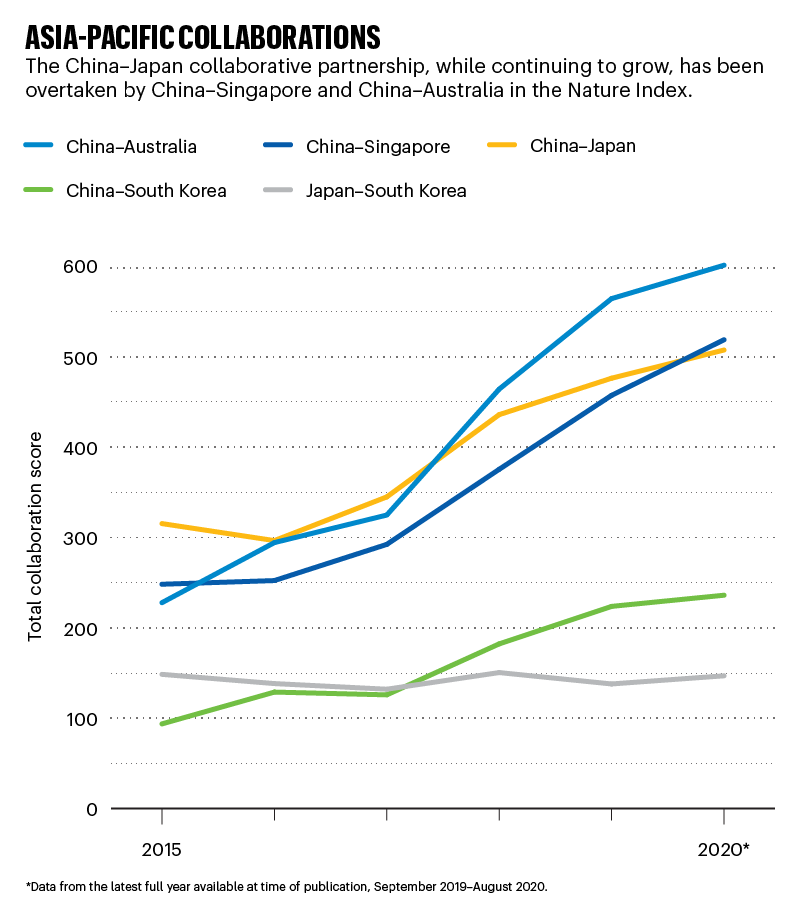

Shin’s efforts are illustrative of the best way collaborations between South Korean scientists and their Japanese colleagues have developed, based mostly on private relationships, somewhat than on account of a government-led initiative. The two international locations have the sixth best collaborative partnership within the Asia-Pacific area within the Nature Index. Compared with different regional partnerships, it’s stagnant, with the amount of their shared output comparatively unchanged since 2015. Both Japan and South Korea have a lot faster-growing, extra productive collaborative partnerships with their mutual neighbour, China.

Diplomatic relations between South Korea and Japan have deteriorated over the previous few years, particularly since 2018, when South Korean courts dominated in favour of compensation for Japan’s use of compelled labour in 1910 to 1945, when the Korean peninsula was a Japanese colony. In 2019, Japan imposed new commerce restrictions on South Korea, and South Korea responded with controls on exports to Japan.

There are not any present government-led massive scientific frameworks to advertise bilateral collaboration. Science and know-how ministers of South Korea, Japan and China met for the primary time in seven years in 2019, however they solely agreed to sort out problems with widespread concern, reminiscent of local weather change, by current mechanisms.

A commerce dispute between the 2 international locations occurred in 2019, when the Japanese authorities tightened controls on exports of three semiconductor supplies (fluorinated polyimide, photoresists and hydrogen fluoride) to South Korea. That transfer hit South Korea’s high-tech trade exhausting as a result of its chip producers relied on imports from Japan. It prompted South Korea to strengthen its R&D practices to spice up self-reliance, particularly in analysis on new supplies and elements, says So Young Kim, director of the Korea Policy Center for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, a analysis group at KAIST in Daejeon. But, she provides, “I believe governments don’t intend to cut off all the relationships. Rather, they want to maintain research collaborations as a completely separate matter from political tensions.”

Takahiko Sasaki, a supplies scientist who additionally oversees analysis ethics at Tohoku University, says the Japanese authorities’s motion has little affect on educational analysis. His college’s relationships with South Korea have been unaffected by political manoeuvring, he says.

According to the most recent Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development figures, Japan spent 3.28% of GDP on science and know-how in 2018, in contrast with 4.53% in South Korea. Both international locations plan to drive their economies by the pandemic with innovation. For 2021, Japan’s foremost finances on science and know-how analysis edged up 0.8% from 2020 to ¥1.35 trillion (US$12.Eight billion). Last July South Korea introduced its ‘New Deal’ plan to spend 160 trillion gained (US$133 billion) by 2025 on a inexperienced and digital financial transformation, boosting spending on science and know-how past the allocation that’s set to double the National Research Foundation of Korea’s (NRF) finances for fundamental analysis to 2.5 trillion gained within the 5 years to 2022.

The comparatively modest worldwide collaboration frameworks already in place work effectively, says Hiroshi Nagano, a visiting researcher specializing in worldwide scientific insurance policies on the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies in Tokyo. For instance, since 2005, the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and the NRF, together with the National Natural Science Foundation of China, have been working the A3 Foresight Program to assist two trilateral tasks yearly. Projects underneath means embody empowering jap Asian elders to make use of the Internet of Things, and the appliance of atomic-scale natural and inorganic supplies. The JSPS and the NRF handle small-scale funding schemes to assist collaborations. “Government-led frameworks do not always lead to good papers,” Nagano says. He says selling individual-based actions is much less delicate to politics and results in productive analysis.

Fusion analysis is without doubt one of the most energetic fields for bilateral collaborations. The National Institute for Fusion Science (NIFS) in Gifu, Japan, and the Korea Institute of Fusion Energy in Daejeon name for brand spanking new proposals yearly for collectively operated collaborative programmes which have run since 2005. Katsumi Ida, coordinator of the Japan–Korea bilateral programme on the NIFS, says the truth that researchers in each international locations don’t have a tendency to alter jobs between analysis establishments has been a bonus in establishing a long-term relationship. Another profit is the comparative ease of exporting analysis tools to South Korea. Such exports to China, against this, are topic to strict controls.

Territorial points typically trigger complications for marine scientists, nonetheless. For instance, the shallow channel between Japan and South Korea known as the Tsushima Strait by Japan and the Korea Strait by South Korea. Last 12 months, Naoki Hirose, a researcher in marine present monitoring at Kyushu University in Fukuoka, Japan, wished to make use of ‘the Tsushima/Korea Strait’ within the title of a paper written with South Korean collaborators. But Japanese funding officers have been nervous a couple of damaging authorities response, and it took two months to steer them, Hirose says. “Such trouble happens sometimes. But the island of Kyushu and the Korean Peninsula are so close to each other. If we cannot get along, that would mean the end of good collaboration for both countries.”

It’s much less fraught within the Antarctic Ocean, the place Jinyoung Jung, an oceanographer on the Korea Polar Research Institute in Incheon, South Korea, is working with Japanese scientists to know the affect of worldwide local weather change on polar oceans. He collected sea-water samples and despatched them to Shigeru Aoki, one among his collaborators at Hokkaido University in Japan, who measured steady oxygen isotopes to estimate glacial meltwater fractions. Their first joint paper is underneath evaluation. In it, they recommend fluorescent dissolved natural matter is a helpful tracer to determine glacial meltwater and circumpolar deep water, a mix of the world’s oceans, which causes glacial melting within the Amundsen Sea in western Antarctica, the place different broadly used chemical tracers reminiscent of steady oxygen isotopes are absent.

Meanwhile, Japanese researchers are sometimes aboard South Korea’s superior icebreaking analysis vessel ARAON, conducting collaborative analysis within the Arctic Ocean. “Combined use of our expertise and capacities brings mutual benefits, which we would not have otherwise,” Jung says.

Koji Shimada, a local weather oceanographer on the Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology and a pioneer of Japan’s Arctic analysis, favours grassroots collaborations between particular person researchers over worldwide consortia pushed from the highest down. “The foundation of country-to-country collaborations should be individual-based projects, as seen in Jung’s work. To nurture such projects will lead to greater outcomes.”