A 340-metre-wide space rock named Apophis whizzed safely past Earth on 6 March. The next time it returns, in 2029, won’t be so uneventful: Apophis will come within 40,000 kilometres of the planet, skimming just above the region where some high-flying satellites orbit. It will be the first time that astronomers will be able to watch such a big asteroid pass so close to us.

Last week’s fly-by gave scientists a chance to test the worldwide planetary defence system, in which astronomers quickly assess the chances of an asteroid hitting Earth as they follow its path across the night sky. “It’s a fire drill with a real asteroid,” says Vishnu Reddy, a planetary scientist at the University of Arizona in Tucson who coordinated the observing campaign.

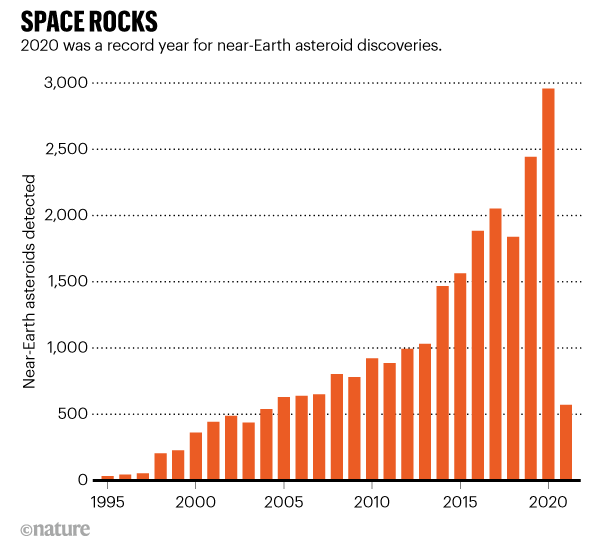

The Apophis fly-by highlights how much astronomers have learnt about near-Earth asteroids — and how much they still have to learn. Since 1998, when NASA kicked off the biggest search for near-Earth asteroids, scientists have detected more than 25,000 of them. And 2020 turned out to be a record year for discoveries. Despite the COVID-19 pandemic interrupting many of the surveys, astronomers catalogued 2,958 previously unknown near-Earth asteroids over the course of the year (see ‘Space rocks’).

A large number came from the Catalina Sky Survey, which uses three telescopes in Arizona to hunt for threatening space rocks. Operations closed briefly last spring because of the pandemic, and a wildfire in June caused a longer closure, yet the Catalina survey still discovered 1,548 near-Earth objects. These included a rare ‘minimoon’ named 2020 CD3, a tiny asteroid less than 3 metres in diameter that had been temporarily captured by Earth’s gravity. The minimoon broke away from Earth’s pull last April.

Another batch of discoveries last year — 1,152 — came from the Pan-STARRS survey telescopes in Hawaii. The finds included an object named 2020 SO, which turned out to be not an asteroid, but a leftover rocket booster that had been looping around in space since it helped to launch a NASA mission to the Moon in 1966.

Close calls

Some of the asteroids discovered last year came close to Earth — at least 107 of them passed the planet at a distance less than that of the Moon. Last year’s close shaves included the tiny asteroid 2020 QG, which skimmed just 2,950 kilometres above the Indian Ocean in August. That made it the closest known approach — a record broken just three months later by another small object, 2020 VT4. That one passed less than 400 kilometres from the planet, and wasn’t spotted until 15 hours after it had whizzed by. Had it hit, it would probably have broken apart in Earth’s atmosphere.

All of these discoveries are making astronomers more conscious of the billiard-ball nature of the Solar System, where plenty of asteroids ping around in the space near Earth. The recent push to observe Apophis highlights how astronomers around the world can work together to assess the threat posed by asteroids, says Reddy. “It’s been a huge international effort,” he says, “and a lot of fun.” By the time Apophis comes around again, in eight years’ time, scientists will have an even more detailed census of threatening space rocks.